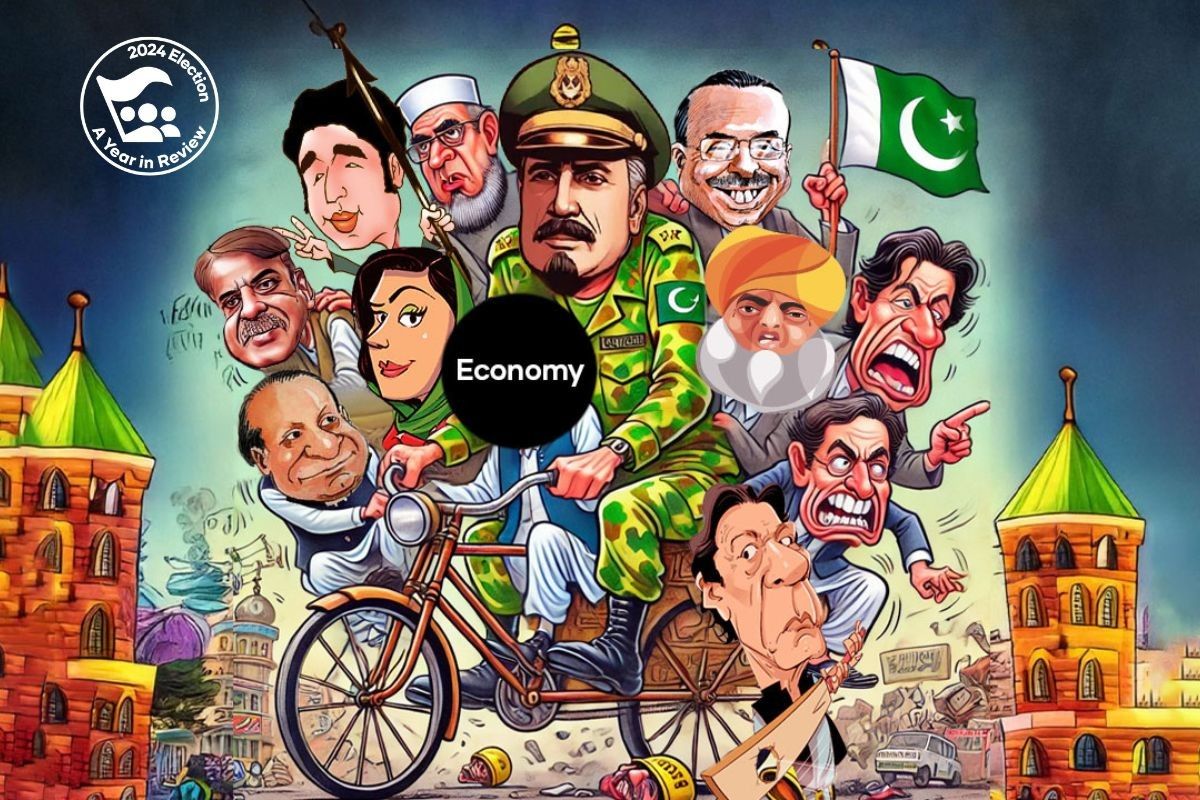

Break the cycle

A year after the 2024 elections, Pakistan's politics is less about new beginnings and more about unresolved endings

Amber Shamsi

Pakistan Editor

Amber Rahim Shamsi is an award-winning multimedia journalist, political commentator, and free speech advocate with extensive experience in media development. She previously served as Director of the Centre for Excellence in Journalism (CEJ) at IBA, where she spearheaded the launch of iVerify Pakistan, a UNDP-supported fact-checking platform. A former BBC World Service bilingual reporter, she has hosted three major current affairs shows on Pakistani news channels. She is also an IVLP and ICFJ Digital Fellow, a media trainer, and an advocate for press freedom and gender representation in journalism.

There’s a new grand opposition alliance in town, calling for fresh elections, railing against the stolen mandate of the people.

The punditry is debating whether the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) will be able to woo Maulana Fazlur Rehman or whether the government will be able to offer a former ally a political bone. But fatigue has set in: Grand opposition alliances and their efficacy have become a fixture of the media noise.

Because these are details.

Why Imran Khan chose to write a letter to the army chief, how he did it, and what it means, are also details. The failed negotiations between the PTI and the government, how many meetings, demands presented and rejected - details. The extent of electoral manipulation in 2024 (Form-47 government) compared to 2018 (the RTS government)? At this point, it doesn’t even matter.

In Pakistan legitimacy isn’t granted through the voter, but through the army, the courts, and international dealings. There is a weary acceptance that elections are merely performative.

The army has so far shown little interest in withdrawing its support - it has got the facade of democracy without the mess. Through the 26th Amendment, the existing regime has managed the courts.

The international community continues to treat Pakistan as a low-democracy, economically high-risk state. For optics, the government hosted the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s meeting in October last year. We are still in the midst of the International Monetary Fund’s loan program. The details of human rights violations and stolen mandates are immaterial.

The Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) has comfortably ingratiated itself with the army despite losing its vote bank - Shahbaz Sharif is no Nawaz Sharif or Imran Khan to rock the boat. Its uneasy ally, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), continues to play the double game - occasionally voicing complaints but ultimately acquiescing, whether it is the 26th Amendment, or the social media laws, all the while biding time for an opportunity.

For its part, the PTI has tried to resist through the streets, the courts, through opposition alliances, through social media, and through limited international pressure. These have largely failed - not just because the regime has gotten its claws into the system of checks and balances - but because the objective of the resistance appears to center on a person rather than an idea.

In writing a letter to the army chief, Imran Khan has only affirmed that he cannot be a symbol for the restoration of democracy when he is a part of the problem.

The problem is Pakistan’s democracy roughly has a 10-year cycle. Dictatorship in the 80s, fragile democratic governments in the 90s, dictatorship in the 2000s, and then another fragile democratic period when governments completed their full terms in the 2010s.

The country entered its hybrid era in 2018 with Imran Khan as a conduit, a system that was supercharged under Shahbaz Sharif. The military remains a key player, managing foreign relations, economic deals, and, when needed, the political temperature.

So Pakistan’s politics, a year after the 2024 elections, is less about new beginnings and more about unresolved endings. Hopes for a reset have given way to familiar patterns of power struggles. Hybrid 2.0 has to yield diminishing returns for all the players involved in order for the cycle to be broken. As yet, it is unclear whether that would be a black swan event or long-term economic unsustainability.

Comments

See what people are discussing