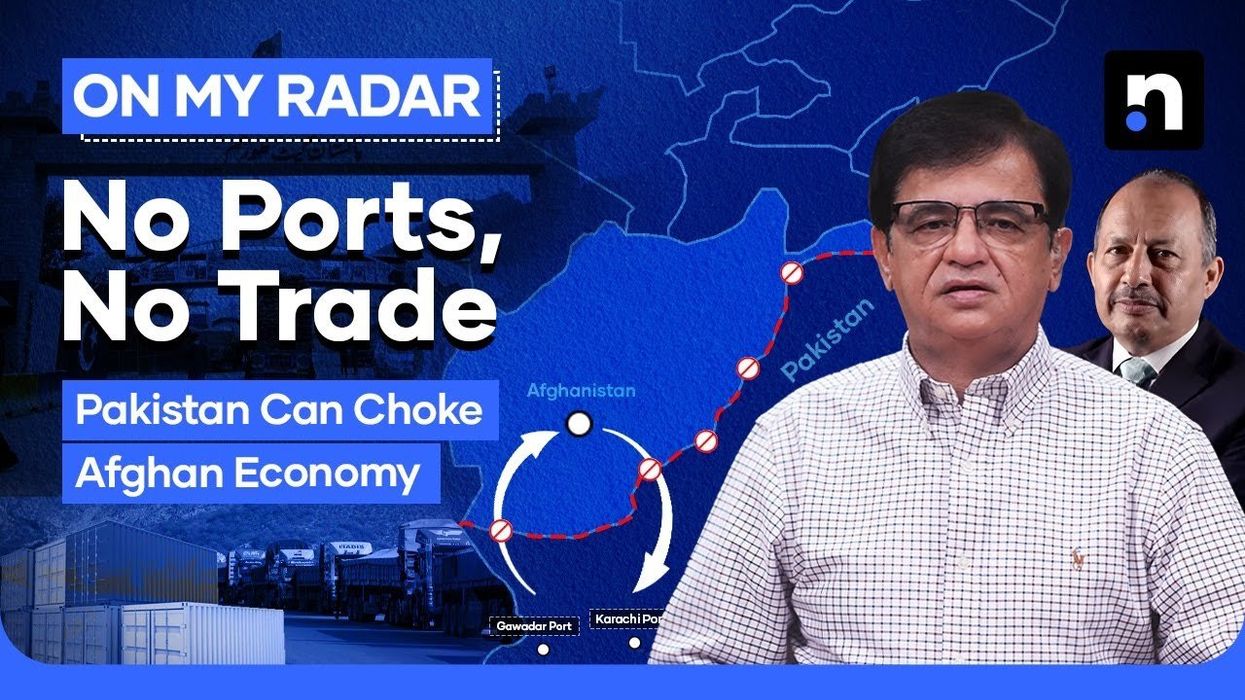

Taliban’s confrontation with Pakistan imperils Afghan economy

Kamran Khan says Afghanistan must remember its economy depends on Pakistan which can cut off that link anytime

News Desk

The News Desk provides timely and factual coverage of national and international events, with an emphasis on accuracy and clarity.

Afghanistan’s growing tensions with Pakistan have begun to threaten its fragile economy, as cross-border trade remains partially suspended following deadly clashes along the Durand Line earlier this month.

The disruption, compounded by U.S. sanctions on Iran’s Chabahar port, has left Afghanistan nearly cut off from two of its key southern trade corridors, heightening fears of an impending economic and humanitarian crisis.

In the latest episode of On My Radar, Kamran Khan said Afghanistan’s continued hostility toward Pakistan - particularly its ties with the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) - could “strangle its own economy.”

He noted that after the October 11-12 border skirmishes and Pakistan’s retaliatory strikes on TTP hideouts inside Afghanistan, the landlocked nation’s trade and supply routes came under what he described as “a virtual siege.”

Pakistan’s leverage over Afghan trade

Following defense ministry-level talks in Doha, Pakistan has begun easing some restrictions by partially reopening the Chaman border. Islamabad has also expressed conditional willingness to restore other crossings within 48 hours. However, analysts say Pakistan could, if provoked, completely choke Afghan trade, as seen during the ten-day closure of land and sea routes that brought Kabul’s commerce to a standstill.

Meanwhile, Iran’s Chabahar port - built with Indian investment and once seen as a major alternative to Pakistan’s ports - has been rendered ineffective under renewed U.S. sanctions. This double blow has left Afghanistan’s external supply lines severely constricted, exposing its dependence on Pakistan’s geography for economic survival.

Although Pakistan ranks third among Afghanistan’s import partners - after Iran (29%) and the UAE (19%) - it remains the country’s largest export destination and logistical artery.

According to the World Bank, 41% of Afghanistan’s exports in the first half of 2025 went to Pakistan. Out of roughly $2 billion in annual Afghan exports, around 70% move through Karachi, Port Qasim and Gwadar, leading observers to describe Pakistan as Afghanistan’s “economic lifeline.”

Khan said that by allowing the proscribed TTP to operate on its soil and launch attacks into Pakistan, the Taliban government has “cut its own trade artery.” He added that Kabul now appears to realize that its uncompromising policies and militant ties could push it toward political instability, economic isolation, and a deepening humanitarian crisis.

A looming humanitarian and economic crisis

The closure of five key trade crossings - Torkham, Chaman, Kharlachi, Ghulam Khan and Angoor Adda - over the past ten days resulted in thousands of dollars in losses for Afghan traders, as perishable goods such as grapes, pomegranates, and vegetables spoiled at the border. Prices of essential commodities in Kabul markets have surged amid supply disruptions.

Despite the friction, Afghanistan’s trade also benefits Pakistan through customs revenue, tolls, and employment for transporters and laborers. The Federal Board of Revenue estimates that Pakistan earns nearly PKR 4.68 billion annually in customs duties from bilateral trade.

Pakistan exports rice, cement, medicines, medical equipment, and food items to Afghanistan, while importing fruits, coal, and dry fruits at relatively lower prices. Still, officials insist that the safety of Pakistan’s 250 million citizens and national security remain paramount.

Afghanistan’s attempts to reduce its dependence on Pakistan through the Iranian route have failed, as sanctions have driven away global shipping, logistics, and insurance firms from Chabahar. The Taliban’s hopes of expanding trade with India via that corridor have also faded, while plans to enhance connectivity with Central Asian republics remain largely confined to discussions.

Even though alternative routes through Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan exist, they involve long overland hauls, multiple border crossings, higher transport costs and security risks - all of which make trade expensive and unsustainable.

Observers warn that if Pakistan’s land routes and seaports, along with Chabahar, remain closed permanently, Afghanistan could face an economic collapse.

Most of Afghanistan’s imports consist of food and medicines, and any prolonged disruption could trigger inflation, shortages, and a humanitarian crisis.

Trade taxes are also a major source of revenue for the Taliban government, and even ten days of disruption have shaken its financial base. Analysts also fear an increase in smuggling, drug cultivation, and black-market activity if formal trade remains blocked.

With both the Pakistani and Iranian trade corridors constrained and trust at an all-time low, Afghanistan stands on the brink of severe economic isolation. The Taliban leadership now faces a decisive moment - to curb its ties with the TTP and rebuild economic cooperation with its neighbors, or risk turning its trade blockade into a full-blown humanitarian disaster for its 34 million citizens.

As Kamran Khan summarized, “Afghanistan must remember that its trade lifeline is tied to Pakistan and if Pakistan chooses, it can choke that lifeline completely.”

Comments

See what people are discussing