Pakistan Supreme Court judges contest release of internal meeting records

Justices Muneeb and Mansoor said the release defied a binding embargo, calling it another case of lawful decisions being ignored

Ali Hamza

Correspondent

Ali; a journalist with 3 years of experience, working in Newspaper. Worked in Field, covered Big Legal Constitutional and Political Events in Pakistan since 2022. Graduate of DePaul University, Chicago.

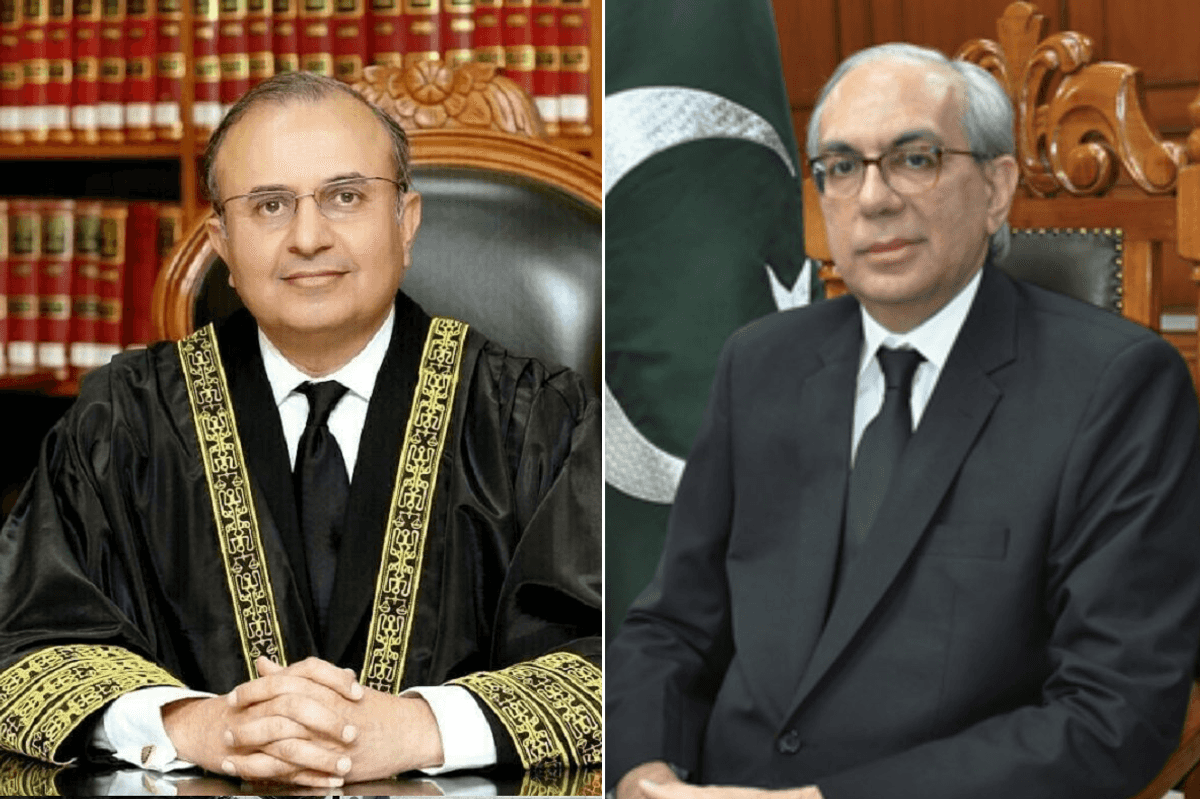

Photos of Supreme Court Justices Mansoor Ali Shah (left) and Muneeb Akhtar.

X

Two senior judges of Pakistan’s Supreme Court have challenged the release of internal court meeting minutes, calling the disclosure misleading, unlawful, and a breach of binding judicial decisions.

In a detailed statement, Justices Muneeb Akhtar and Syed Mansoor Ali Shah objected to the publication of minutes from the Supreme Court’s Practice and Procedure Committee - particularly those of October 2024 - which were made public nearly 10 months later despite an earlier decision by the committee to keep them confidential.

They argued that releasing the records ignored a binding embargo imposed by the committee’s majority, describing the move as yet another instance of lawful decisions being disregarded.

The judges maintained that the October 31 meeting was a valid session and that its outcomes - especially the directive to hold a full court hearing on challenges to the 26th Constitutional Amendment in early November - were legally binding.

The full court hearing, approved by a 2–1 majority including Justices Akhtar and Shah, never took place. Instead, Chief Justice Yahya Afridi recorded in the minutes that under the 26th Amendment, the authority to set a hearing date now rested with a constitutional bench or committee.

The two judges accused the chief justice of bypassing the committee through private consultations with judges - a process they said had “no legal basis.” They also alleged that the court’s registrar failed to implement the committee’s directive, while the chief justice circulated private notes dismissing the decision, none of which were shared with them at the time.

One such note, they said, was even read out during a Judicial Commission of Pakistan meeting in November, even though the commission - tasked with nominating judges - had no authority to override the committee’s decision.

Warning of “grave legal consequences,” Justices Akhtar and Shah said the failure to convene a full court at a pivotal moment undermined the Supreme Court’s credibility and deprived it of a collective, legitimate response to the constitutional petitions.

They concluded that the petitions against the 26th Amendment remain unresolved because of this failure, noting that a historic opportunity to settle the issue through a full court may have been lost “perhaps irretrievably.”

The judges demanded that their letter be published on the Supreme Court’s website alongside the disputed minutes, declaring: “If the record is now in the public domain, at least let the record be complete.”

The 26th Constitutional Amendment, passed by parliament in October 2024, shifted the authority to appoint Pakistan’s Chief Justice from the most senior judge of the Supreme Court to a special parliamentary committee.

Why it matters

Advocate Supreme Court Shah Khawar told Nukta that divisions within the Supreme Court are confusing litigants and eroding public trust. “Internal matters must be resolved under one roof and not dragged into the public domain,” he said.

Khawar, who has practiced before the Supreme Court since 2008 and seen 12 chief justices, called the rifts troubling. He said judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts share responsibility not to publicize minutes or issue open letters.

On the judges’ letter, he noted two key points: the absence of a full court hearing on the 26th Amendment and the missed chance for a collective constitutional response. “A constitutional response was urgently needed and should have been given,” he stressed.

Citing Article 5 of the Constitution, which requires loyalty to the state and obedience to law, Khawar said that while the 26th Amendment may have flaws, it remains valid legislation and must be followed by all citizens.

By contrast, constitutional expert Hafiz Ehsaan Ahmad Khokhar said the 26th Amendment fundamentally reshaped court procedures by introducing Article 191A, which overrides earlier laws and practices.

He explained that Article 191A assigns specific cases to a Constitutional Bench and creates a separate committee for other matters. With these provisions in force, the earlier Practice and Procedure Committee ceased to exist. The Chief Justice was therefore justified in not convening it or calling a full court meeting, he said.

Calling it “legally misconceived” to claim no constitutional bench or committee was formed, Khokhar argued the Constitution takes precedence over prior laws or practices. “The CJP acted rightly under this framework,” he said.

On the judges’ letter, he said the views expressed contradict the clear language of Article 191A and do not align with the constitutional mandate. Differences of opinion are natural, he added, but should not create an impression of institutional division. “This letter is part of an internal debate, but the Constitution remains binding — not notes or individual views,” he emphasized.

Khokhar concluded that the Chief Justice acted within the Constitution and that, after the 26th Amendment, Article 191A must remain the Supreme Court’s ultimate guide.

Comments

See what people are discussing