Why thousands are fleeing Pakistan’s northwest again

More than 25,000 people have been displaced from Pakistan’s Tirah Valley, with numbers expected to reach 150,000 by Jan. 25

Kamran Ali

Correspondent Nukta

Kamran Ali, a seasoned journalist from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, has a decade of experience covering terrorism, human rights, politics, economy, climate change, culture, and sports. With an MS in Media Studies, he has worked across print, radio, TV, and digital media, producing investigative reports and co-hosting shows that highlight critical issues.

The Tirah Valley has long seen unrest, with TTP-linked and other militant groups prompting repeated military operations.

Nukta

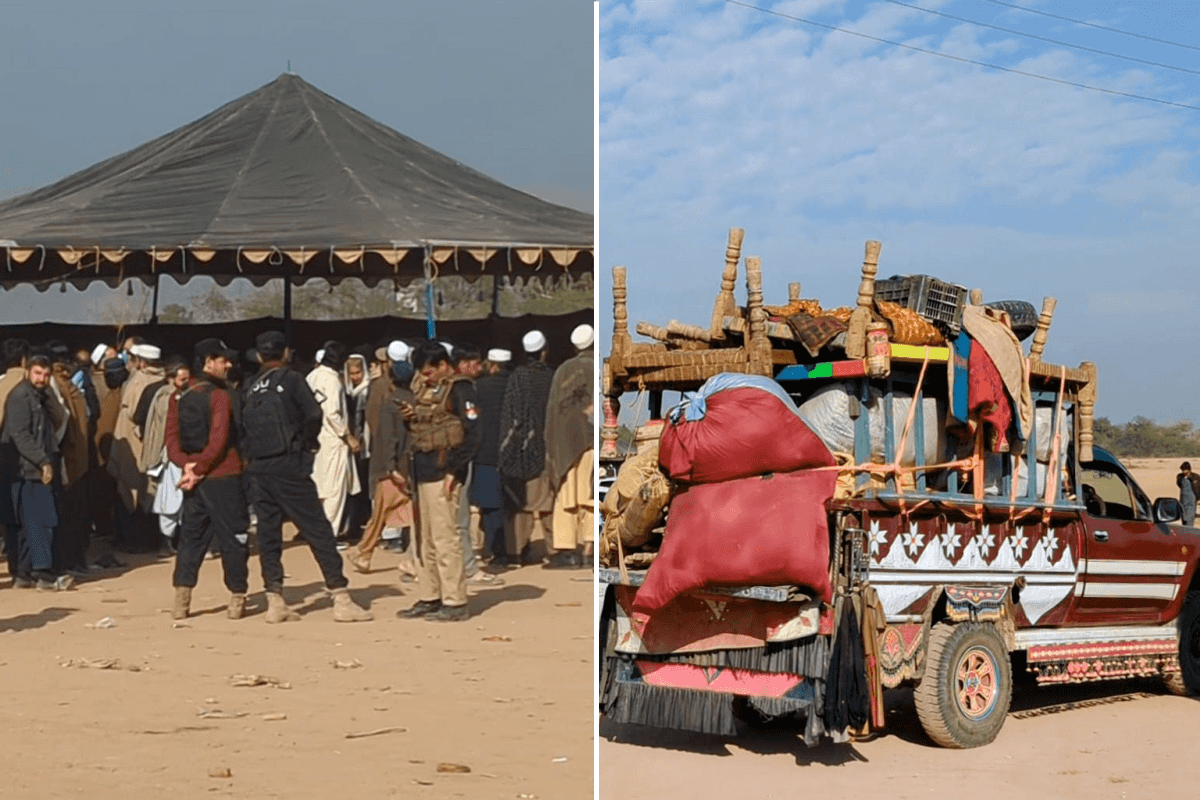

Fifty-year-old Muhammad Yaseen still recalls the day his life unraveled amid the crackle of gunfire, falling bombs and incoming shells. “Even the walls of our own home offered no sanctuary,” he said, describing the violence that forced him to flee Pakistan’s remote Tirah Valley.

Now, he stands in a long queue at a relief distribution point in Mandi Kas in Khyber district, shivering in the winter cold as weak sunlight offers little relief. Around him, hundreds of others wait for assistance, their lives upended by the latest surge of conflict in Pakistan’s volatile northwest.

“This is not our first exile,” Yaseen said, reflecting a cycle of displacement that has marked the region for decades. Many of those now seeking aid have been uprooted before by earlier military offensives against Taliban-linked and other armed groups. Each return home, residents say, has been tentative, while every new conflict further drains their savings and resilience.

Scrambling from a restive valley

Yaseen is among more than 25,000 people recently displaced from the mountainous Tirah Valley, a long-troubled area along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Authorities estimate that the number of displaced could rise to 150,000 by Jan. 25.

The displacement follows a military operation aimed at clearing militant factions that have taken shelter in the area. The operation has triggered a fast-moving humanitarian crisis, forcing families to flee with little notice and limited access to food, shelter and medical care.

War’s collateral damage

For those forced to leave, the cost of war is measured less in distance travelled than in what is left behind. “We had a house worth 30 to 40 million rupees,” Yaseen said. “Our three-storey home was left behind. Now we have nothing.”

He said his family abandoned belongings spread across several vehicles because they could only arrange a single truck for the escape.

Another displaced resident, Hayatullah, said the journey itself compounded the hardship. “We spent four to five days on the road, staying in vehicles,” he said. Authorities had promised rent assistance and compensation, he added, “but we have received neither.”

The lack of immediate support has left displaced families vulnerable to exploitation, Hayatullah said. Many escaped with little more than basic furniture such as beds and sleeping cots, leaving most of their possessions behind.

Sanctioning aid, not blame

Iqbal Afridi, a lawmaker from Khyber district representing the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), said elected representatives had not been taken into confidence over reports of a military operation or the resulting displacement.

Speaking to Nukta, Afridi said the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) provincial government had not authorized the action and described it as a “forced operation,” for which he said his party did not accept political responsibility.

However, he stressed that the displaced families were “their own people” and said the provincial government would provide all possible assistance.

The KP government has publicly stated it was unaware of any such operation and had not approved it. At the same time, the province’s finance department has released four billion rupees in financial assistance for those displaced from the Tirah Valley, according to an official notification.

Displacement timeline

District officials and tribal elders said a formal evacuation plan had been put in place. Before hostilities escalated, authorities convened a jirga, or traditional council, with representatives from the Tirah Valley to coordinate a managed evacuation and later rehabilitation.

Under the agreed framework, evacuations began on Jan. 10 and are expected to continue until Jan. 25. The phased return of displaced families is planned to start about two months after military operations conclude.

The compensation package provides a one-time payment of PKR 250,000 to each displaced family, along with a monthly assistance of PKR 50,000. It also includes compensation of three million rupees for fully destroyed homes and one million rupees for partially damaged houses, subject to post-operation assessments. Authorities are also responsible for providing transport, medical care and food supplies along evacuation routes.

Relentless cycle

Unrest in the Tirah Valley is not new. For years, alongside the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), groups such as Lashkar-e-Islam have maintained a presence in the area, prompting repeated military operations. Large-scale offensives in 2008 and 2014 triggered mass displacements, with returns often taking years.

Since 2020, a sustained campaign of targeted operations has kept security fragile. That tenuous balance collapsed in recent months following the shooting of protesters last year, an alleged airstrike that residents say killed dozens, and a rise in militant drone and direct attacks on security forces - events authorities cite as the trigger for the latest and most disruptive, operation.

Comments

See what people are discussing