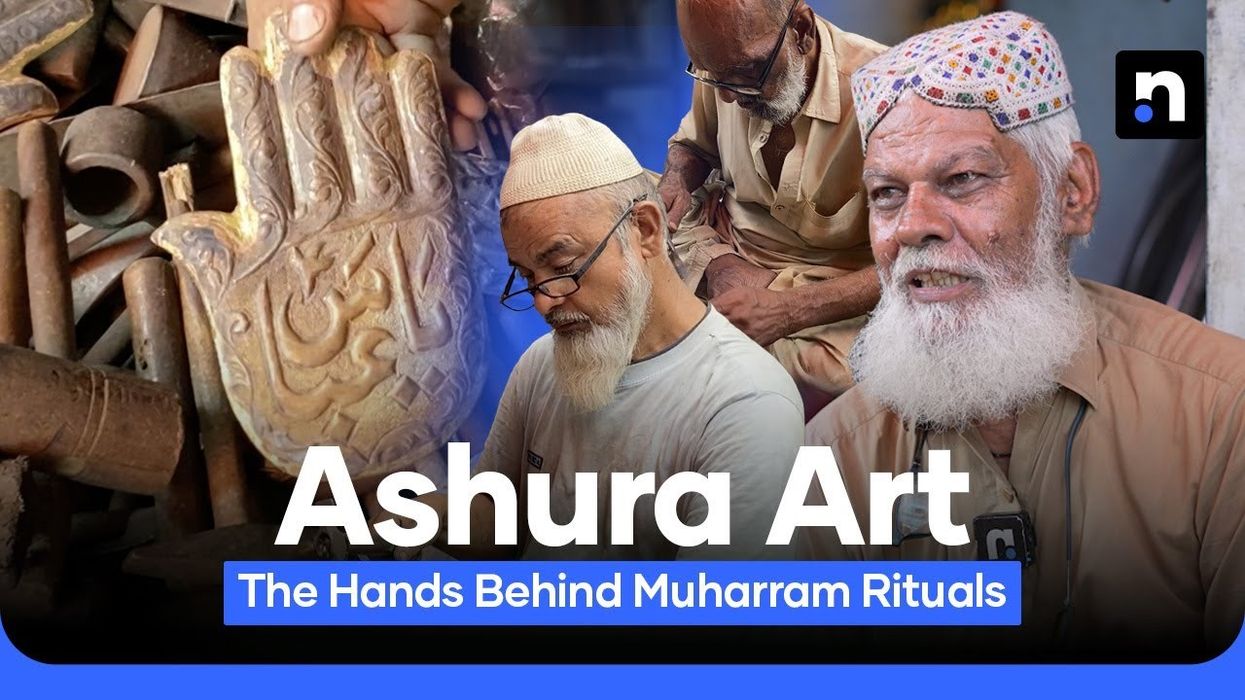

From Jaipur to Karachi: The living art of Muharram craftsmanship

In Karachi’s Lalukhet, Partition-era artisans keep a fading sacred tradition alive by handcrafting intricate Muharram symbols, blending devotion, heritage, and livelihood

Shumaila Khan

Chief Correspondent

Shumaila Khan, a multimedia journalist and Chevening SAJP fellow with 17+ years of experience, is known for her acclaimed work with BBC Urdu, BBC Indian Languages, DW English, Dainik Bhaskar, UNICEF, and Internews.

In the densely packed lanes of Lalukhet, a neighborhood in Karachi that still carries echoes of Partition-era migration, a small, dimly lit workshop resonates with the soft clang of hammer on tin.

The air is warm, almost reverent, as three elderly men sit cross-legged, hunched over sheets of raw metal, etching intricate motifs into the surface with a precision that borders on sacred ritual. With the month of Muharram underway—a time of mourning and remembrance for Shia Muslims—this modest space becomes a cradle of devotion, where centuries-old craftsmanship meets unshakable faith.

This is the domain of 70-year-old Imam Deen, a master artisan whose hands have shaped the religious symbols that line procession routes across Pakistan.

With a chuckle and a shake of his head, he gestures to his two companions—his younger brother Noor Uddin, 65, and longtime friend Amano, 71. "We’ve all grown old doing this work," he laughs, "but since we do it with devotion, it has become like ibadat. Rozi bhi hai, aur ibadat bhi hai—it’s both our livelihood and our worship."

The objects that emerge from their hands—alam panjas, tazias, jhoolas, zarih mubarak, and ornate accessories for Zuljinah, the symbolic horse of Imam Hussain—are more than decorative.

They are expressions of grief, reverence, and a deep historical continuity. As Muharram begins, the volume of work increases dramatically, and the small workshop turns into a production line of reverence.

"Orders start coming in well before Muharram begins," says Imam Deen, whose family has been in this trade for generations. His father, who migrated from Jaipur during the Partition, carried not just memories but also a legacy of sacred art. Imam Deen, now flanked by his own sons, has continued that tradition since the 1980s.

"Back then, we used to make alams in silver. They weren’t made in such large numbers either. Today, the demand has increased and the designs have become more elaborate. We used to make smaller tazias; now they’re huge."

Despite the surge in demand, the process remains entirely manual. The artisans source tin and raw metals from cities like Lahore and Gujranwala, which are then cut and engraved in Karachi using hand tools.

Mechanization, Imam Deen insists, would be antithetical to their work. "We don’t use machines because each customer comes with different budgets and specifications. It's not possible to create a separate mold for each order. Every piece is crafted based on weight and cost."

The costs, however, have changed dramatically. "There was a time when you could buy an alam for 500 to 1,000 rupees. Now, due to inflation, it costs around 10,000 rupees per kilogram," Imam Deen says. And though orders have grown—coming from all over Pakistan and even from abroad—the number of skilled artisans is shrinking. "There used to be only a handful of people making these. Now, the craft is expanding, but craftsmen are becoming scarce."

The items themselves have evolved. "Earlier, only the panjas of Imam Hussain (AS), Haider (AS), and Abbas (AS) were common. Now, people request the names of many revered figures. Even the symbolism in processions has expanded—more items are being created under the name of alam, and more accessories for Zuljinah are being produced."

Among his many creations, Imam Deen takes particular pride in the Jhoola Shahzada Ali Asghar, a symbolic cradle that he builds every year. "From the doors of main Imambargah in Ancholi, to the zari for Buturab Imambargah and the Masoomeen Imambargah, and even the latticework for Sehwan’s shrine—they’re all my handiwork," he says with visible pride.

And yet, for all its beauty, the work is not without its frustrations. Chief among them is Karachi’s unreliable electricity. "When the power goes out, polishing and finishing come to a halt," he laments. "We can’t do puffing or buffing properly. That delays everything."

Despite these challenges, Imam Deen has never advertised his craft. "I’ve never taken my work to the market," he says. "My customers always come to me." It’s a quiet testimony to the trust and reputation he’s built over decades—one intricate design, one engraved panel at a time.

In a city of shifting skylines and fast-paced change, the workshop in Lalukhet remains a steadfast shrine to tradition. Here, artistry and faith are inseparable. Here, devotion is hammered into every curve of metal. As Imam Deen puts it, "This isn’t just work. It’s a legacy. It’s a prayer."

Comments

See what people are discussing