In Pakistan’s Parachinar valley, peanuts speak louder than violence

In a valley long shadowed by violence, Parachinar’s peanuts have become a symbol of resilience, prized for their flavor, size, and the livelihoods they quietly sustain

Kamran Ali

Correspondent Nukta

Kamran Ali, a seasoned journalist from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, has a decade of experience covering terrorism, human rights, politics, economy, climate change, culture, and sports. With an MS in Media Studies, he has worked across print, radio, TV, and digital media, producing investigative reports and co-hosting shows that highlight critical issues.

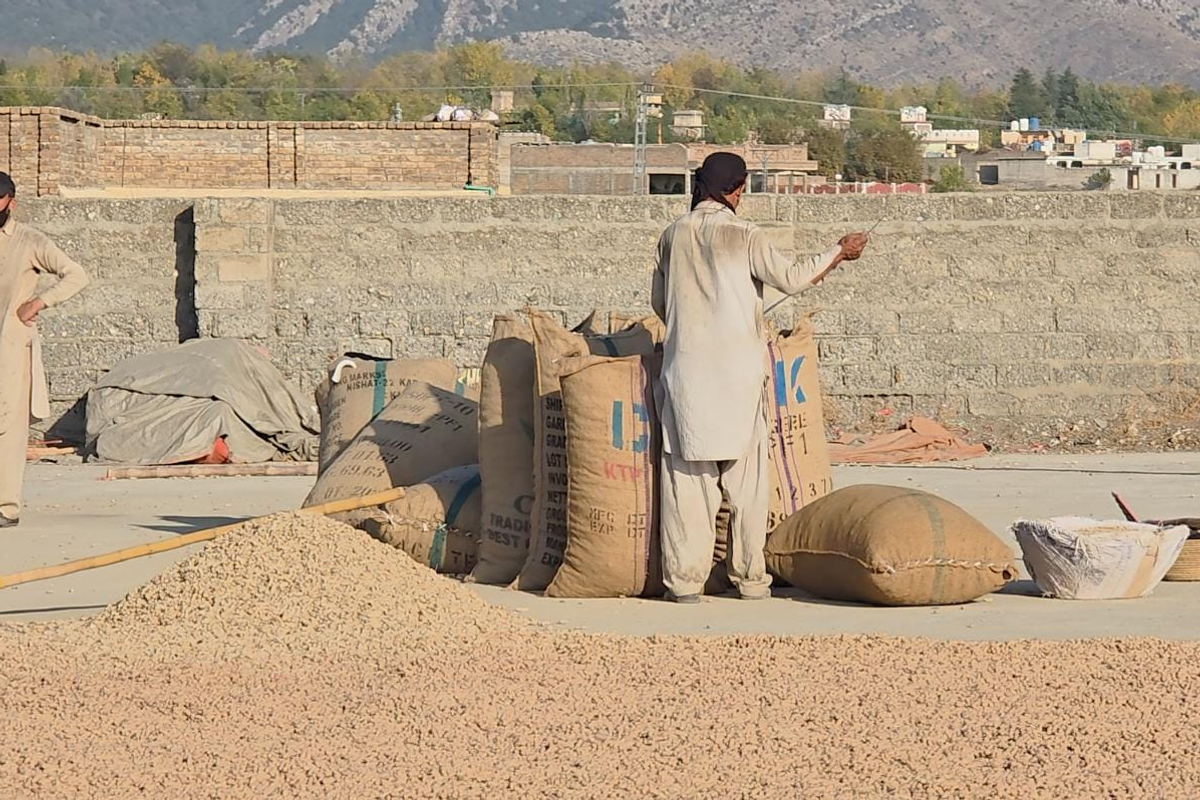

On a cold morning in Pakistan’s Parachinar valley, farmers crouch low over soil that has learned to endure more than weather. Here, in a high-altitude pocket along the Afghan border, peanuts ripen quietly underground - unnoticed by the headlines that have long defined the region.

For once, Parachinar is not being talked about for violence. It is being noticed for flavor.

Parachinar peanuts have achieved something rare in Pakistan’s crowded agricultural markets: instant recognition. Larger than most, pale-shelled and richly aromatic, they are traded not just as snacks but as symbols - often wrapped as gifts and carried across cities, borders and seasons.

Their reputation, farmers say, is inseparable from the land itself.

“It’s the climate that does the work,” says Iqrar Hussain, a research officer with the agriculture department.

Cool nights during the pod-forming stage slow the crop’s development, allowing the kernels to mature fully in the soil. The result is a peanut that tastes deeper, crunches cleaner and commands higher prices from Peshawar to Karachi.

Local farmer and seller Mohsin Fakhri has seen demand travel far beyond Parachinar’s green slopes. Each pod, he says, typically carries three to five kernel - more than usual - encased in unusually white shells.

“People recognize them immediately,” he says. The peanuts are sold in sacks across Pakistan’s major cities and exported into Afghanistan, where they compete with Tajik varieties but remain preferred for their size and flavor.

But this season, the story of Parachinar’s peanuts is as much about absence as abundance.

According to official data, Kurram district produced 1,417 tons of peanuts in 2024. Production figures for 2025 are still being compiled, but traders expect a decline. The reasons have little to do with farming technique - and everything to do with fear.

Last year’s sectarian clashes shut down the Thal-Parachinar Road, the district’s main commercial artery. Trucks were stranded. Crops spoiled. Losses mounted.

“Many farmers couldn’t sell what they had grown,” says trader Iqbal Hussain, who typically collects thousands of sacks each season. This year, many planted less, worried the roads would close again. Some did not plant at all.

The pressures have compounded. Lower rainfall and crop diseases have further cut yields, farmers say. The market response has been swift: while regular peanuts sell for PKR 800 to 1,000 per kilogram, Parachinar peanuts now fetch more than PKR 1,500 - a price driven by scarcity as much as quality.

The valley itself carries the weight of recent trauma. In November 2024, a deadly attack on a convoy traveling from Parachinar to Peshawar killed 43 people. The violence that followed claimed over 150 lives, injured hundreds more and severed vital road links, pushing the region into crisis.

Since then, authorities have dismantled private bunkers and disarmed residents. The reopening of the Pak-Afghan Kharlachi border crossing in May 2025 has helped restore limited movement and ease tensions. But stability remains fragile and for farmers, each planting season is a calculation of risk.

Still, the peanuts grow.

Beneath the soil, shielded from uncertainty above ground, they develop slowly - shaped by cold nights, clean air and a geography that refuses to be rushed.

In Parachinar, where conflict has long overshadowed craft, a simple crop has become a quiet counter-narrative: proof that even in places defined by disruption, the land continues to produce something worth protecting.

Comments

See what people are discussing