Pakistan’s MQM confronts new era as founder abolishes loyalty pledge for workers

Experts say MQM-London is unlikely to regain its former stature, with all factions in London and Pakistan sharing blame for the party’s decline

Razi Wani

Producer - News Desk

Razi Ud Din Ahmed Wani is a multimedia journalist and digital storyteller with a strong background in fact-checking, South Asian politics, documentary filmmaking, scriptwriting, and digital content production. With an MA in Mass Communication from the University of Karachi, he has experience directing and scripting web series and socio-political satires. And has worked across various media and digital platforms, focusing on emerging trends and storytelling formats.

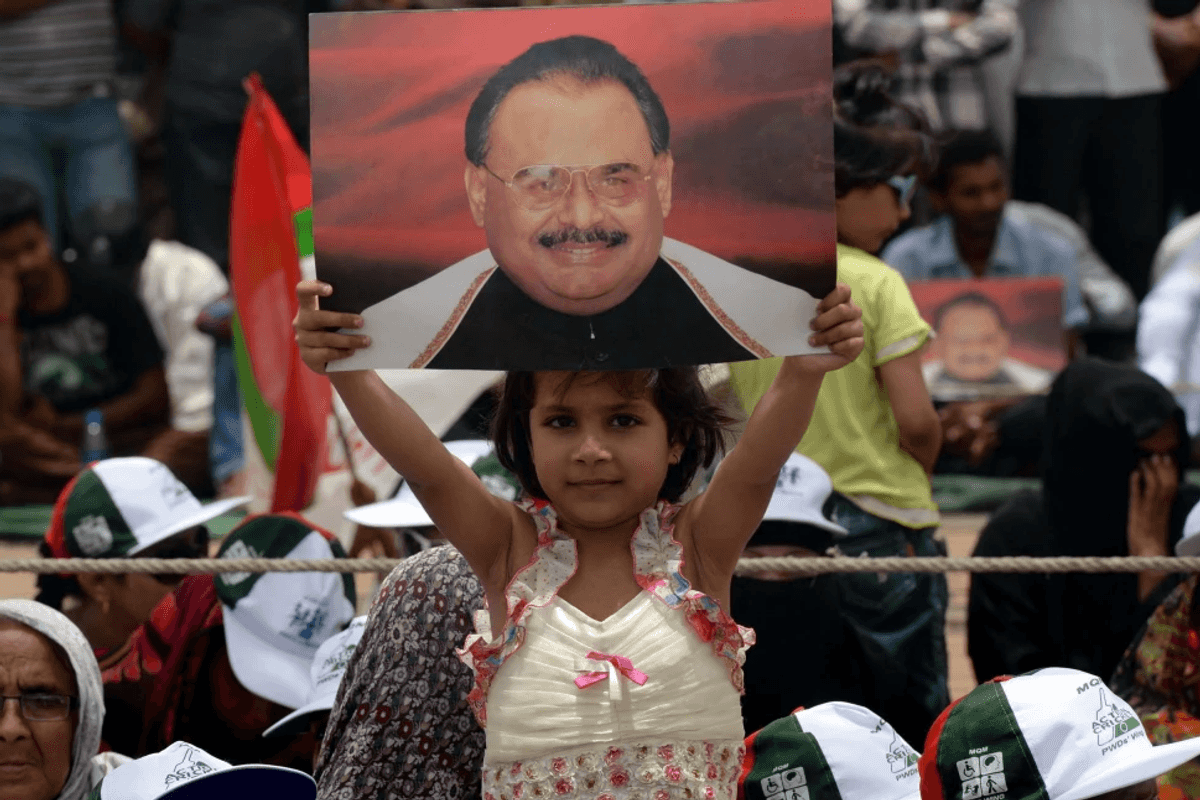

A young girl from Pakistan's Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) party holds a photograph of party leader Altaf Hussain during a sit-in protest calling for Hussain's release in Karachi on June 6, 2014.

AFP/File

Altaf Hussain, the exiled founder of Pakistan’s Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) and once the undisputed political powerbroker of Karachi, has formally released his supporters from the decades-old oath of loyalty to him and the party.

The announcement - made from London, where he has lived in self-imposed exile since 1992 - is being seen as the symbolic end of a political era that shaped urban Sindh for nearly four decades.

Speaking via video link to a virtual gathering of followers on Monday, Hussain acknowledged that he had failed to “secure political rights” for Pakistan’s Urdu-speaking Muhajir community, descendants of those who migrated from India after the 1947 Partition.

“I release all movement companions… from the oath of loyalty,” he declared in a statement shared on X, adding that his struggle would now continue online “as long as I am alive.” He reflected on decades of political struggle, the thousands of “martyrs” claimed by the movement, and personal losses, including the killings of his brother and nephew.

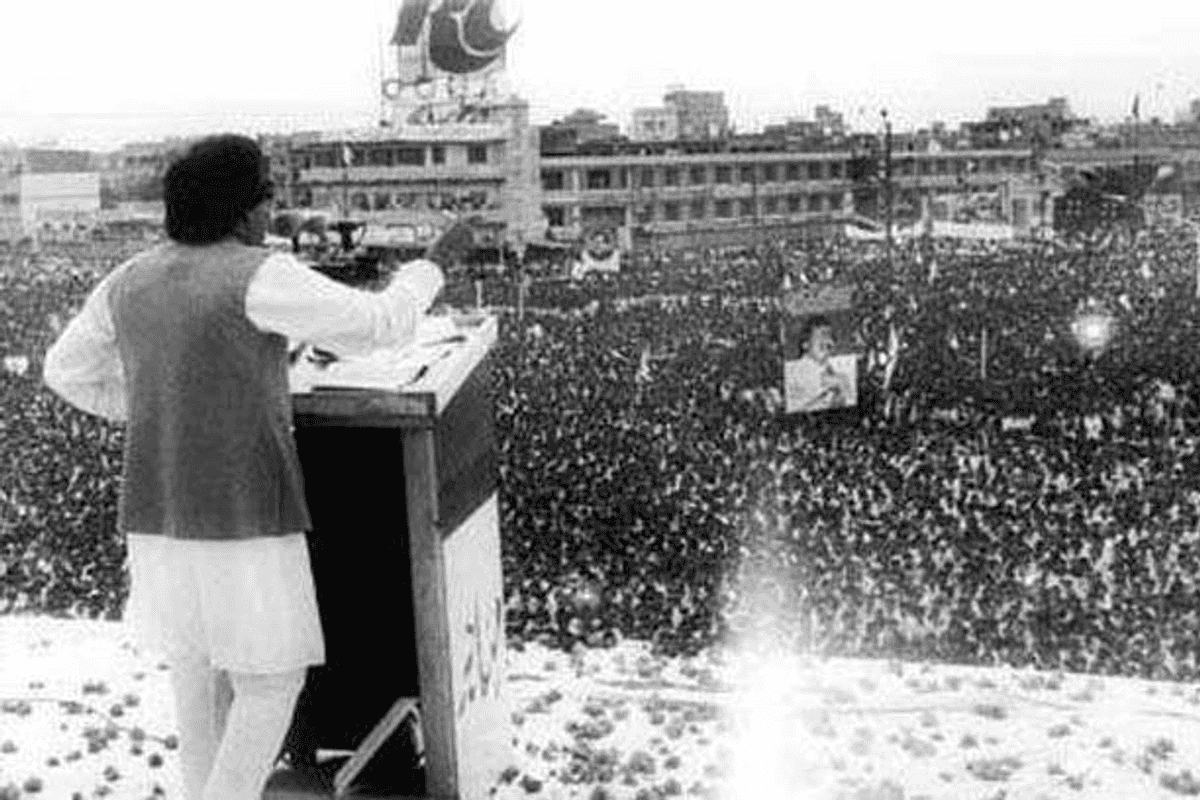

For a man who once addressed tens of thousands in Karachi by telephone from thousands of miles away, the announcement marks the quiet closure of a chapter defined by fervent devotion, street power, and bitter political rivalries.

From student activism to political powerhouse

MQM traces its roots to the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organization, which Hussain launched in the late 1970s. It formally became the Mohajir Qaumi Movement in 1984, gaining prominence after ethnic riots erupted in 1985 following the Bushra Zaidi incident, when a young student’s death sparked violent unrest.

Sweeping Karachi and Hyderabad’s local elections in 1987, MQM quickly became a key political player. In 1988, it allied with the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) in a short-lived partnership that collapsed in 1989 after violent clashes.

The party then joined Nawaz Sharif’s Islami Jamhoori Ittehad, securing a coalition role after the 1990 elections.

The relationship ended in 1992 when the Pakistani military launched “Operation Clean-Up” amid terrorism allegations. Hussain fled to London that January, never to return, and later gained British citizenship.

In the years that followed, MQM boycotted the 1993 national elections but swept the Sindh provincial polls, once again joining the PPP in the provincial government. In 1997, it returned to an alliance with the PML-N and rebranded itself as the Muttahida Qaumi Movement to broaden its political appeal.

Tensions with the PML-N flared again in 1998 after the assassination of philanthropist Hakim Sayeed, prompting governor’s rule in Sindh and an end to the alliance.

Under Pervez Musharraf’s military-led government, MQM regained influence in 2002 as a coalition partner, enjoying a revival in Karachi’s politics.

Cracks in the alliance network

MQM’s dominance began to strain in 2007 after deadly violence during the Karachi visit of then-suspended chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry. In 2008, the party joined the PPP-led government, but in 2012, its image was dented when London police raided MQM’s UK office during the investigation into the murder of senior leader Imran Farooq.

Hussain’s combative tone toward Pakistan’s judiciary led to contempt of court proceedings, which he avoided with an unconditional apology.

In 2013, MQM quit both the federal and Sindh governments in protest against the PPP, losing ground after a key local government law was repealed. That same year, Hussain came under scrutiny for a televised speech in which he appeared to question Pakistan’s territorial integrity - remarks his allies said were taken out of context.

The 2016 collapse and the split

The real rupture came in August 2016, when Hussain delivered a fiery speech reportedly critical of Pakistan and calling for unrest. Shortly afterward, MQM workers attacked a private news channel’s office, prompting a broad crackdown.

Party offices were sealed, leaders in Pakistan publicly distanced themselves, and a “minus-Altaf” formula removed his name from the MQM constitution.

This split created two factions - MQM-Pakistan, led by Farooq Sattar and Khalid Maqbool Siddiqui, and MQM-London, loyal to Hussain. While MQM-Pakistan remained an active political force, its dominance in Karachi weakened amid leadership purges, internal disunity, and growing competition from rivals such as the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI).

It was during this turbulent period that senior MQM figure Mustafa Kamal broke away to form the Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP) in 2016. Despite a high-profile launch, PSP struggled to gain political traction or secure meaningful representation.

By January 2023, Kamal merged PSP with MQM-Pakistan - a faction that retained roots in the original movement but had severed ties with its founder. Today, Kamal has re-emerged as one of the most prominent faces of MQM-Pakistan and serves as a federal minister.

Inside the cult of loyalty

Kamal has openly described the party’s once-unquestioning devotion to Hussain. “We were practically worshipping him,” Kamal said in a podcast with Kamran Khan earlier this year. “We even used sticks to make the public follow suit… We acted like lunatics.”

Critics within the Muhajir community were often branded “Jamaatis,” and dissent was met with hostility. Kamal admitted that despite calls from senior figures to evolve into a national political force, MQM remained tightly bound to its ethnic base.

Decline, irrelevance, and Karachi’s uncertain future

Veteran journalist Mazhar Abbas told Nukta that MQM-London became politically irrelevant after August 22, 2016, and faced an undeclared ban on political activities in Pakistan. “Even their sector and unit offices in London were not allowed to engage in political work, and all this was unofficial,” he said.

“Until 2013, he [Hussain] enjoyed considerable support. But it’s too early to say what impact today’s announcement will have… It appears he has become largely irrelevant to Pakistan’s politics,” Abbas noted, adding that both Hussain’s conduct and the state’s actions contributed to his downfall.

He suggested the latest move might be an attempt to re-energize his shrinking base. “In the past, Hussain has made similar statements - announcing retirement or stepping away from politics - only to reverse them,” he said. “His health is poor, and his name comes up far less in political discourse.”

Abbas believes MQM-London will not regain its former stature. “Today, MQM is in disarray, and all factions - whether in London or Pakistan - share responsibility. The politics they began has now reached its conclusion.”

Looking at Karachi’s electoral map, Abbas recalled how the city once served as an opposition stronghold before PTI’s 2018 victory broke MQM’s grip. But the city’s direction, he said, remains uncertain.

It seems unlikely that any single party will once again hold the representative status in Karachi that MQM once did. In the near future, no clear representative party for urban Sindh is on the horizon.

Adding to this assessment, senior analyst Nasir Baig Chughtai said Hussain’s remarks suggest he is stepping back due to illness and perhaps recognizing that his political role has effectively ended "after years of mistakes".

He noted that MQM’s influence had already eroded when Hussain kept the party under tight control and discouraged participation in key activities like some local elections. “The ‘Altaf factor’ no longer exists on the ground,” he said, recalling how MQM’s image once likened its workers to “angels” for Karachi and Hyderabad before circumstances deteriorated, forcing Hussain into exile.

Chughtai argued that while MQM’s manifesto - particularly its stance on ending the quota system and securing rights for urban Sindh - held real significance, it failed because the party repeatedly joined governments and compromised.

The issue is not just whether the Muhajir community got its rights, but that even the common man in Pakistan has yet to get his due - and those who fought for it were killed.

As for Karachi’s future, he said, “The city’s solution lies in strong national parties like PPP and JI, while PTI has effectively committed political suicide here. Karachi needs a good party – will it come? I don’t think so.”

Comments

See what people are discussing