Did CPEC really change Pakistan’s game?

Contrary to what was expected, growth path was not jolted by CPEC. In fact it has nose dived in some sectors

Asad Ejaz Butt

Guest Contributor

Asad Ejaz Butt is an economist based in Boston, US. He tweets @asadaijaz.

Sectors that CPEC was expected to turn around have inched downwards instead of improving.

AI generated

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) was launched with opulent grandeur in 2013. The program was dubbed a game changer for Pakistan, and this was a narrative not only sold excessively by the Pakistani government to its people but also bolstered immensely by the Chinese authorities. But did it change Pakistan’s game?

Well, it arguably did not. Those supporting CPEC concede that Pakistan is not where it ideally should have been, but ask two deterministic questions to substantiate their argument. In hindsight, wouldn’t any policymaker, regardless of their position on the political spectrum, latch onto a project like CPEC given the extraordinary economic prospects it presented? And wouldn’t Pakistan have descended further in the last decade had there been no CPEC?

It’s difficult to answer such deterministic questions, but Pakistan’s economy hasn’t had the best of times, and the sectors that CPEC was expected to turn around, industrial manufacturing and energy, have inched downwards instead of improving.

Pakistan's government celebrated the 10-year anniversary of CPEC in 2023. It provided a progress update of the projects being implemented under CPEC, but did not really analyze whether it was able to achieve the policy and economic objectives it aspired to achieve through CPEC. As I will argue in this piece, the projects seem to be doing very well, but not CPEC or the Pakistani economy, which it vowed to change.

I remember being part of two evaluation reports on CPEC published by the Burki Institute of Public Policy (BIPP) in 2017 and 2018.

At the launch of the 2018 report in Islamabad that was chaired by then newly elected Finance Minister Asad Umar, my long-time colleague and friend Mustehsan Abbas, an Australian-Pakistani finance expert, who was then an instructor of finance at a private university in Lahore, asked a simple yet very thoughtful question.

He asked the authors of the report that we are often told that CPEC is a game-changer for Pakistan, and around 20 percent of all its projects are complete, so has Pakistan’s game changed by 20 percent?

That question stayed with me and continues to rip apart the government's claims about the projects, most of which have been completed, as the government rightly claims, but not ‘taken off’. Why did they not take off, and why did the game not change would require a more detailed diagnostic of what went wrong and where. However, this is an opportune time to reflect that when nearly 60 percent of all projects have been completed, Pakistan’s game did not change by as much.

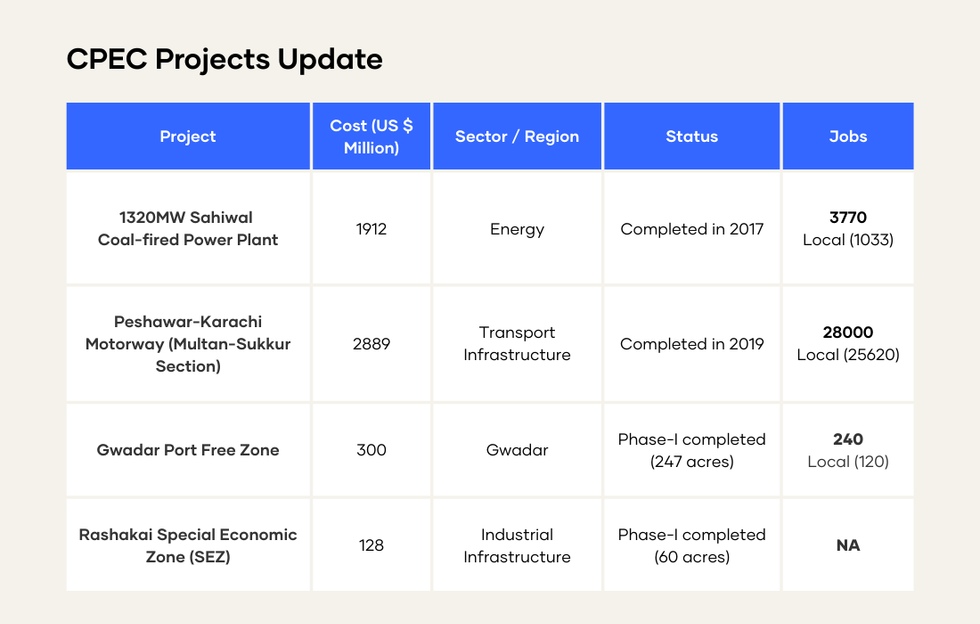

I have selected the largest CPEC project from each of the four sectors marked for implementation by the Planning Commission of Pakistan. These four collectively claim around $5 billion of CPEC investment and seek to generate around 27,000 local jobs in the economy.

The power plants were expected to increase energy supply and stabilize energy tariffs, while the special economic zones had to incentivize industrial production and promote exports.

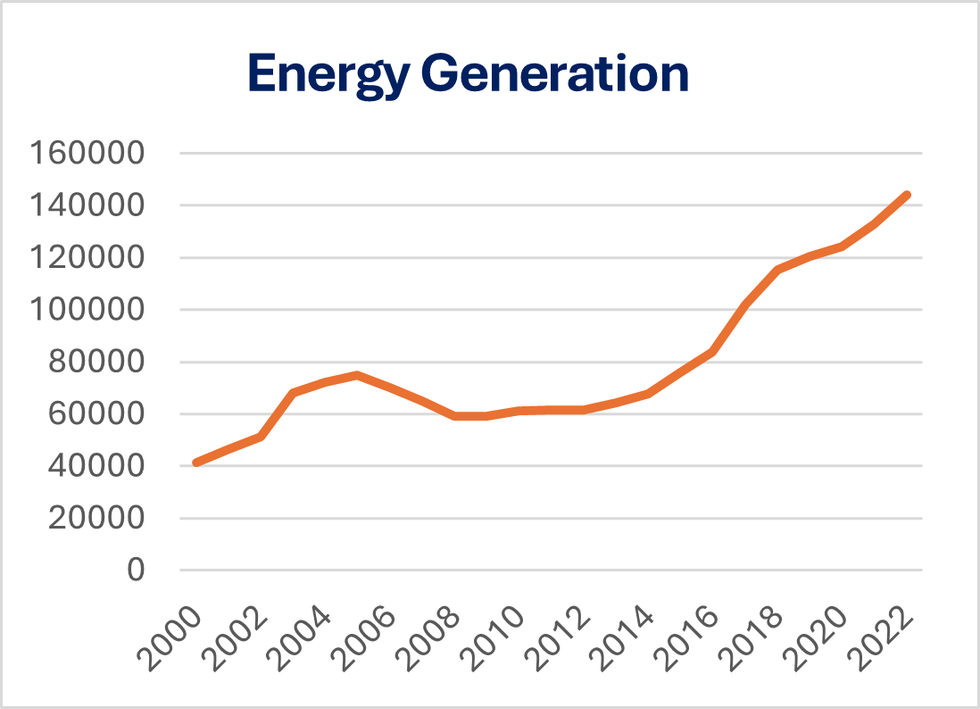

The energy sector consumed the largest part of CPEC investments. Three large-scale and long-gestation projects, each with a generation capacity of 1,320MW alone, cost around US$ 6 billion. Energy supply has increased, but not at the rate at which it could outpace demand and calm down prices.

While energy shortages may have become less frequent over the years, the energy sector has become the problem-child in Pakistan, contributing massively to the country’s current account deficits and a chronic debt problem.

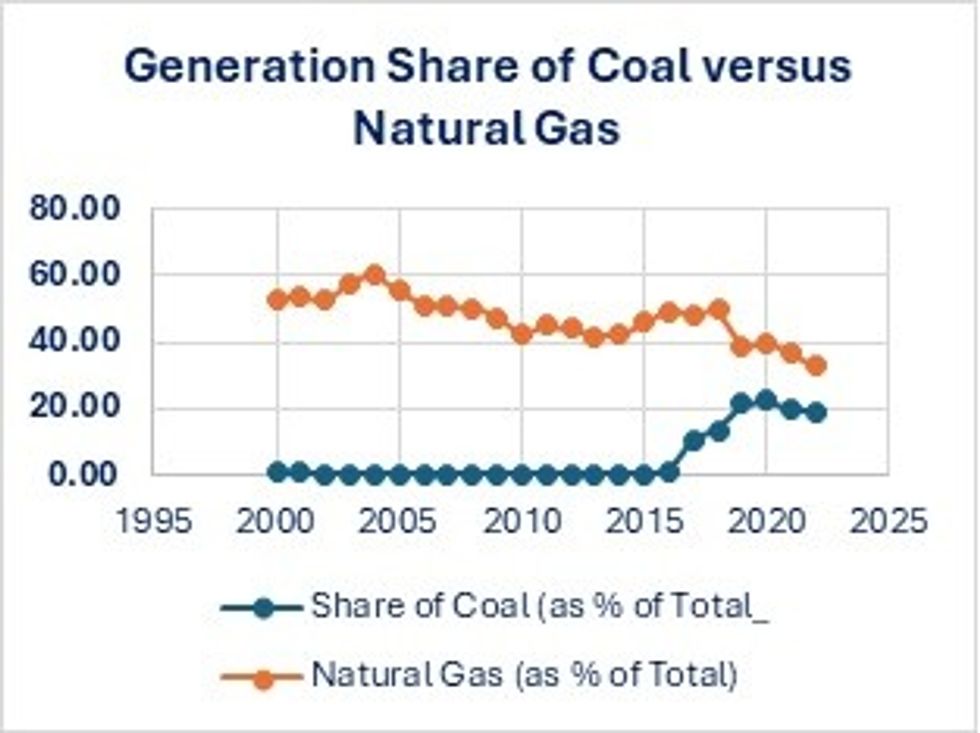

In addition to piling heaps of public debt, CPEC has also adversely altered Pakistan’s energy mix. The Chinese exported coal-fired energy to Pakistan, which has, on the one hand, replaced natural gas, but also limited the potential to shift towards renewable sources.

I have dissected CPEC, connected the dots, and analyzed the economy holistically to arrive at the three charts below. All of these are time-series plots of macroeconomic indicators linked to CPEC.

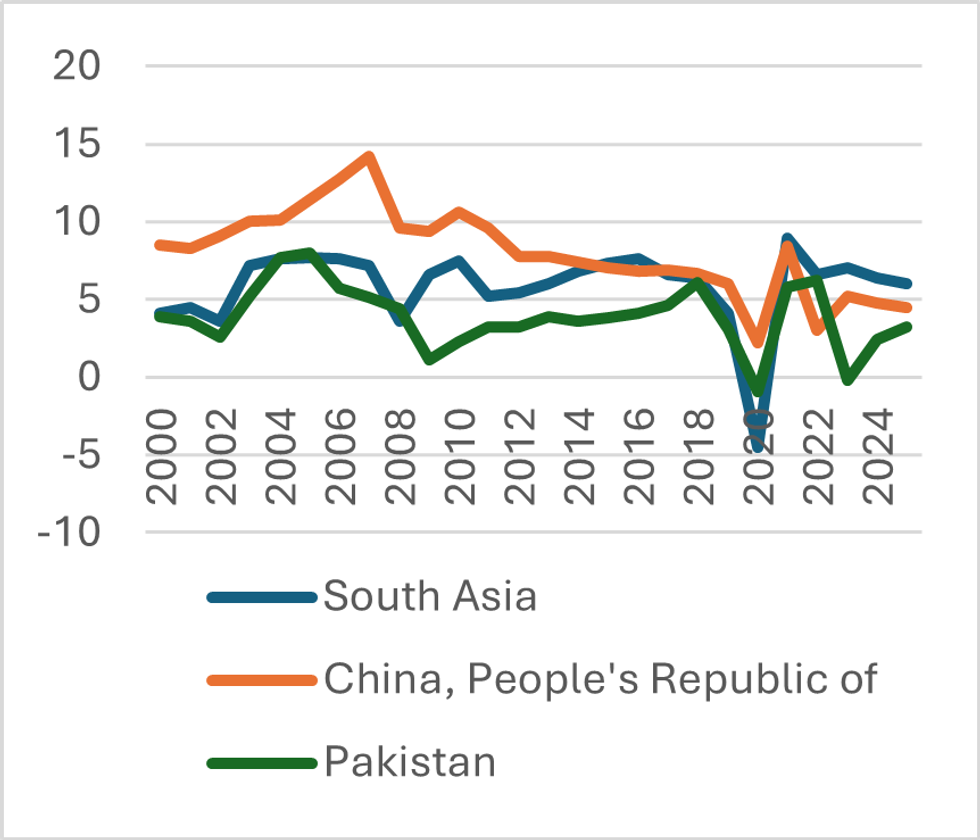

The first is real GDP growth: Pakistan’s inflation-adjusted growth rate is trailing the South Asian average by a significant margin. GDP growth has remained volatile during CPEC as it was in the pre-CPEC time.

But contrary to what was expected, the growth path was not jolted by CPEC. Growth has remained subdued, and in fact, it nosedived in some periods after FY 2019.

One conclusion we can draw from this is that CPEC was not the remarkable propeller of growth that the Pakistanis thought it was. The BIPP estimated in its 2017 annual report that CPEC would add 2% to Pakistan’s annual growth rate.

In many periods after CPEC was launched, overall growth, which included non-CPEC contributors, was less than 2%.

It can be argued that non-CPEC growth was negative in these periods. Therefore, it will be pertinent to separate CPEC from non-CPEC sectors to see how differently the CPEC sectors performed.

I accomplish this goal through the other two charts. I have also plotted Chinese economic growth during the same period, which, understandably so, significantly outpaces Pakistan’s and the South Asian average. It is hard to dispute that they are benefitting enormously from regional integration.

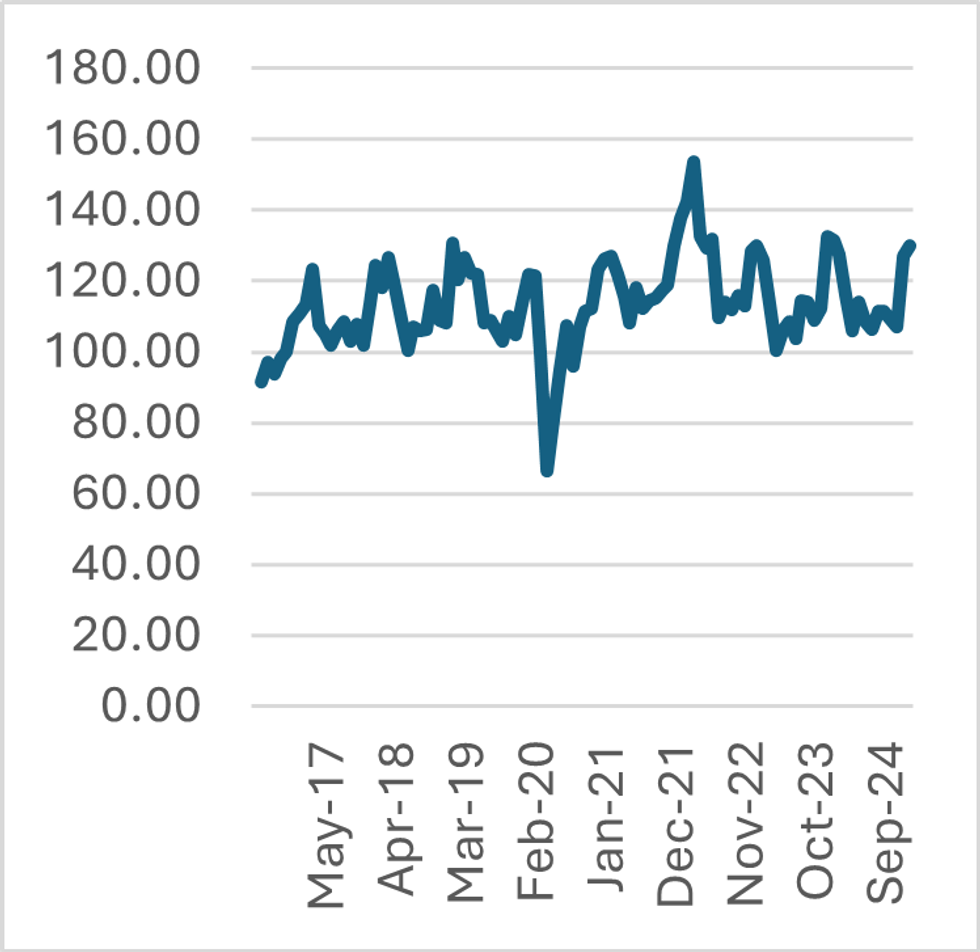

The second chart represents manufacturing output, which also indicates an economy’s capacity to export. The lower line in the manufacturing output chart shows that manufacturing declined as a percent of GDP, only to revive in the recent past, but remains nearly at the level at which it was in 2013-14. The Planning Commission reports that some SEZs have been completed since 2019. Have they added anything to the large-scale manufacturing output? Or exports? Both the SEZs and the energy power plants are massive investment-guzzlers, and their returns indicate that they have lent less to growth than they have to debt.

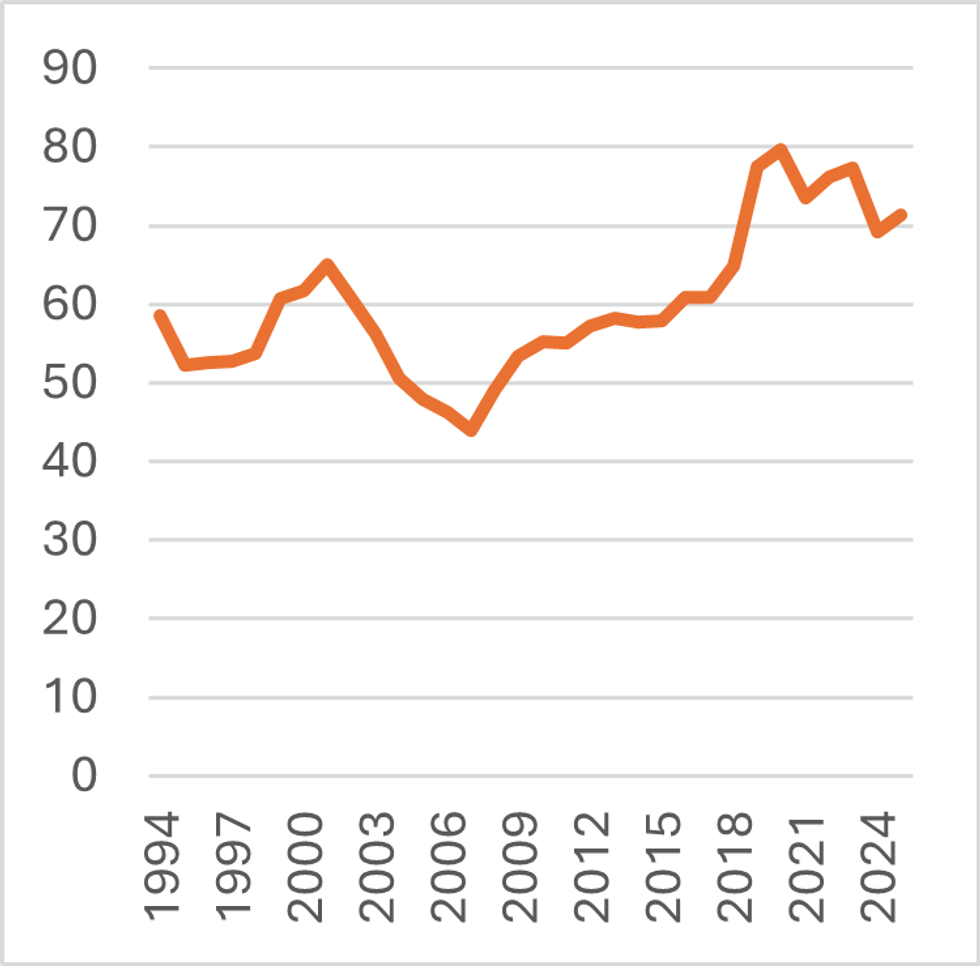

The third chart is the most important: government debt as a fraction of GDP has risen noticeably in the last few years, witnessing a spike since 2015. This gives credence to claims made at the start of CPEC that it is a Chinese neo-imperialist design to indebt Pakistan and use debt as a political instrument.

Well, the Chinese have continued to be killed in Pakistan, and the two countries may have drifted away as opposed to coming closer diplomatically.

China is not the patronizing partner of Pakistan and its allies like the U.S. thought it would turn out to be after CPEC. But CPEC didn’t take off, and Pakistan has also been honoring its debt commitments. But in doing so, Pakistan broke its back. Its external debt has swelled, while it has also developed a domestic debt problem due to the inefficiencies in the energy sector.

Growth has remained stagnant, and the losses of the energy sector have to be financed through deficit budgets, which push the government to indulge in more debt and enter into one IMF program after another. China continues to grow and prosper, and tacitly blames Pakistan for whatever has gone wrong with CPEC.

Now that the government has built these white elephants through borrowed Chinese money, it needs to ensure somehow that they start contributing to the economy. The metros, motorways, SEZs, and power plants cannot be made to sit out there and rot. They have to be used in a manner in which they can facilitate business and commercial enterprise.

*Asad Ejaz Butt is an economist based in Boston, US. He tweets @asadaijaz.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Nukta.

Comments

See what people are discussing