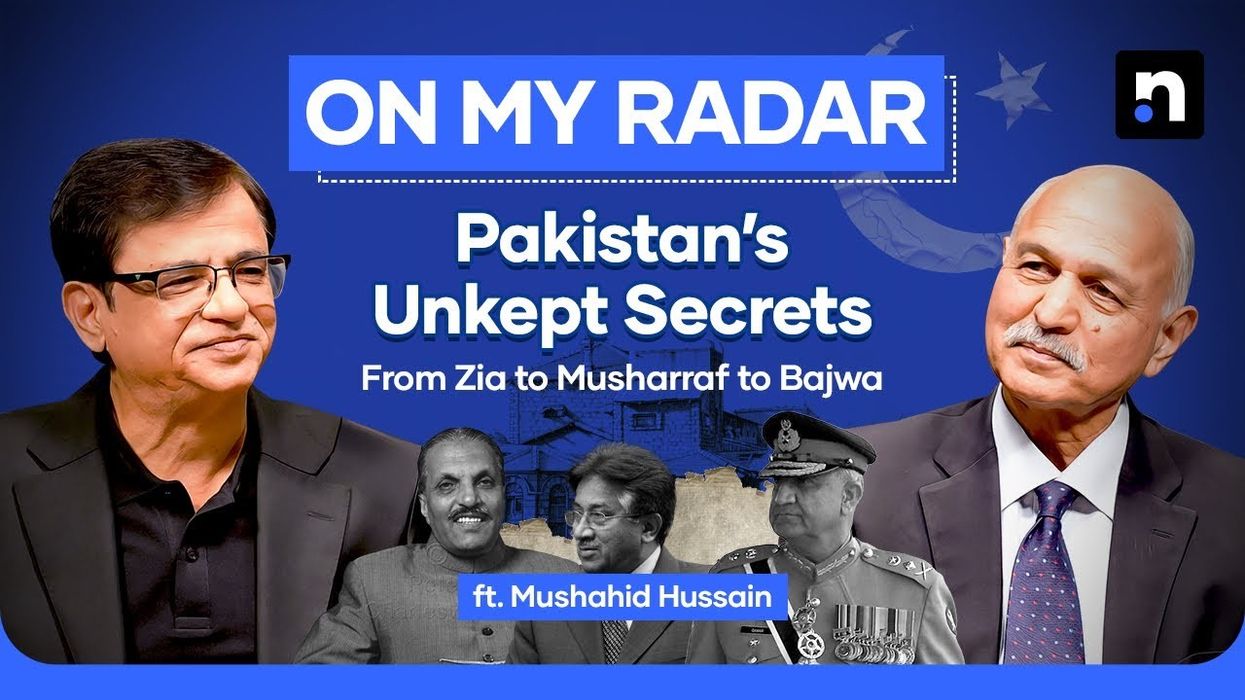

From Afghan jihad to civil-military clashes: Key moments that shaped Pakistan

In a wide-ranging discussion with Kamran Khan, Mushahid Hussain reflects on pivotal moments from Zia’s martial law to Benazir’s leadership and Nawaz’s rise

News Desk

The News Desk provides timely and factual coverage of national and international events, with an emphasis on accuracy and clarity.

Drawing from his experiences as a journalist during General Zia-ul-Haq’s martial law and his later political career, renowned journalist and politician Mushahid Hussain offers a unique perspective on Pakistan’s turbulent journey through military dominance, democratic transitions, and regional conflicts in this candid and wide-ranging conversation with Kamran Khan.

From the establishment of The Muslim newspaper under an oppressive regime to the Afghan jihad, Benazir Bhutto’s tumultuous premiership, and Nawaz Sharif’s evolution as a leader, Mushahid unpacks key moments that shaped Pakistan’s trajectory.

Journalism under Zia’s martial law

General Zia-ul-Haq’s martial law marked a transformative period in Pakistan’s political and media landscape, Mushahid said as he described his era as "the mother of all establishments".

Recalling Zia’s influence, he noted: "General Zia was a bold and commanding military ruler, whose impact on Pakistan’s governance and institutions was profound."

The Muslim newspaper was established against this backdrop, setting new standards in journalism. At the helm of this initiative was Agha Murtaza Poya, who, according to Mushahid, “was an excellent boss who never interfered in our work. Agha Murtaza had an open mind. He was not just a businessman but someone open to intellectual discussions.”

The team at The Muslim was equally remarkable. Mushahid described it as "a brilliant assembly of minds," including prominent leftist Minhaj Burna, star reporter Kamran Khan, literary figures like Khalid Hasan, and experienced journalists such as Javed Bukhari and H.K. Burki.

The inclusion of other notable names, such as Aslam Sheikh, Maleeha Lodhi, Shireen Mazari, and two American women, Carol Pasha and Stephanie Bunker Khan, highlighted the diversity and depth of talent.

Others, like Nusrat Javed, Marianna Babar, Ishrat Hayat, and Rahimullah Yusufzai, also made invaluable contributions.

Mushahid emphasized the shift in editorial roles during his tenure: "Editors in Pakistan used to act like judges—they only read editorials and rarely engaged in reporting. I changed the game. An editor, in my view, should not just smoke cigars and write editorials. I personally started reporting and getting into the field."

The creation of The Muslim was not just the birth of a newspaper but a redefinition of what journalism could achieve under difficult political circumstances.

The Afghan jihad: A tale of collaboration and ambition

The roots of the Afghan jihad were laid during the tenure of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, long before General Zia-ul-Haq became synonymous with the conflict. "It was Bhutto who first invited leaders like Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Burhanuddin Rabbani, Rasul Sayyaf, and Ahmad Shah Massoud to begin operations against the Kabul regime," Mushahid revealed.

General Naseerullah Babar, then the IG of the Frontier Corps, played a central role in these early efforts. According to him, “Only three individuals knew about the operation: Bhutto himself, Army Chief General Tikka Khan, and me.”

To ensure secrecy, even Foreign Minister Agha Shahi was kept in the dark. Babar later explained, "We wanted to avoid putting Shahi in a position where he would have to lie about our activities," Mushahid stated.

During General Zia's era, the Afghan jihad evolved into a large-scale military and ideological campaign. "Zia-ul-Haq maintained tight control over the Afghan jihad. The CIA had no direct contact with the Mujahideen," Mushahid explained. "While the CIA provided money and weapons, it was the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) that decided how these resources were distributed and planned operations."

He added, "The distribution of Stinger missiles to the Mujahideen was entirely handled by the ISI. For the Americans, this was an opportunity to avenge their defeat in Vietnam. The results were clear: no Americans died, the Red Army was defeated, and the Soviet Union eventually collapsed."

However, Mushahid lamented the long-term consequences for Pakistan. "The continuation of flawed policies after the Afghan jihad ended up harming Pakistan more than we could have anticipated." The ambitions did not stop with Zia’s death, as the idea of capturing Jalalabad took center stage.

Benazir Bhutto’s first government: A fragile alliance and fall

The return to democracy in 1988 came with its challenges, especially for Benazir Bhutto, who faced resistance from the military establishment.

Mushahid recounted, "The ISI decided to block Benazir’s path by forming the Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI). But after General Zia’s death, the IJI plan initially failed."

Mushahid criticized the establishment’s tendency to disregard public opinion, stating, "Whenever they try to implement political plans, they fail because they ignore the will of the people." When Benazir emerged victorious, the establishment was reluctant to transfer power, even filing a petition against a woman leading the government.

The U.S. played a significant role in brokering a deal. “President Reagan sent Richard Murphy and Richard Armitage to negotiate what became known as the ‘mother of all deals,’” Mushahid said. This arrangement kept Ghulam Ishaq Khan as President, Benazir as Prime Minister, Yaqub Khan as Foreign Minister, and V.A. Jafri in charge of Finance.

Under this agreement, Benazir conceded Punjab’s governance to Nawaz Sharif while the military retained control over Afghan and foreign policy. Despite these constraints, Mushahid praised Benazir’s determination: "She was influenced but not a puppet."

However, the challenges soon became insurmountable. Mushahid revealed that "money played a central role" in an unsuccessful no-confidence motion against her. Ultimately, her government was ousted through other means, as Nawaz Sharif rose to prominence as the establishment’s preferred candidate.

The Gulf War of 1990 added another layer of complexity. "Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990. Four days later, Benazir’s government was dismissed," Mushahid recalled. Efforts to intervene with Ghulam Ishaq Khan proved futile, as he insisted on acting within constitutional limits.

A pivotal moment came when Benazir replaced General Hamid Gul with retired General Shamsur Rahman Kallu as ISI chief. "This was the first time a civilian Prime Minister took such a step," Mushahid emphasized. The decision marked a turning point, as it signaled Benazir’s willingness to challenge the military establishment—a move that crossed a red line.

Nawaz Sharif: A journey of power, conflict, and resilience

Nawaz Sharif emerged as a pivotal figure in Pakistan’s political landscape with the military establishment's backing after General Zia’s death.

Mushahid noted, “Nawaz became the chosen one to counterbalance Benazir Bhutto.” His political ascent was orchestrated through the IJI, with support from key figures like Generals Aslam Beg and Hameed Gul.

As Punjab Chief Minister, Nawaz built a populist profile through infrastructure projects and pro-establishment rhetoric. However, growing political maturity brought friction.

“Nawaz was initially pliant but started asserting his independence, creating tensions,” Mushahid observed. This period reflects the establishment’s efforts to control governance and Nawaz’s eventual push for autonomy.

Nawaz’s first tenure as Prime Minister revealed cracks in his relationship with the military. Seeking economic and institutional autonomy, he dismissed ISI chief General Javed Nasir, signaling discord. His second term intensified this struggle as he introduced reforms like the 13th Amendment – which stripped the President of the power to dissolve the National Assembly - to consolidate civilian power.

“The Kargil episode highlighted the growing disconnect,” Mushahid noted, with Nawaz excluded from military decisions. His dismissal of General Musharraf in 1999 triggered a coup, marking a dramatic clash between civilian authority and military dominance.

Moving forward, economic revival defined Nawaz’s leadership. “He prioritized industrial growth and privatization,” Mushahid explained, citing privatized banks, steel mills, and telecommunications as key initiatives.

Infrastructure projects like motorways and airports aimed to integrate rural areas and fuel growth. Despite resistance from bureaucracies and unions, Nawaz’s pro-business policies resonated with the middle class, though critics argued they disproportionately favored industrialists. Economic reforms were often undermined by political instability, including sanctions after Pakistan’s nuclear tests in 1998.

The decision to conduct nuclear tests in response to India’s 1998 tests solidified Pakistan’s global standing. “Nawaz faced immense U.S. pressure to refrain,” Mushahid recalled. Despite severe economic sanctions, Nawaz prioritized national security over economic fallout, gaining widespread domestic approval. However, the sanctions’ long-term effects added complexity to his legacy.

Nawaz’s efforts for peace with India, including the Lahore Declaration in 1999, showcased his belief in dialogue despite criticism. Mushahid highlighted, “He envisioned economic cooperation as mutually beneficial.” However, the Kargil conflict derailed progress and strained civil-military relations, with Nawaz blindsided by the military’s unilateral actions.

Following the 1999 coup, Nawaz spent years in exile, using the time to rebuild his political vision and maintain party unity. “Exile shaped his priorities,” Mushahid explained. His return in 2007 marked a renewed focus on democracy and civilian leadership.

Nawaz’s 2013 election win underscored his economic focus, including addressing the energy crisis and launching CPEC. Mushahid highlighted, “CPEC brought investments and jobs, transforming infrastructure.” However, his third term faced challenges, including allegations of corruption and political unrest.

The 2016 Panama Papers leak triggered Nawaz’s disqualification as prime minister, framing him as both a controversial and galvanizing figure. “It was a landmark decision,” Mushahid noted, with Nawaz portraying himself as a victim of undemocratic forces.

Post-disqualification, Nawaz championed the slogan “Vote ko izzat do,” emphasizing respect for electoral mandates. “He became a symbol of resistance,” Mushahid observed, consolidating public support for civilian supremacy.

His imprisonment in 2018 and subsequent exile in London marked significant challenges. “He used his time to maintain party connections and highlight governance issues,” Mushahid noted. Critics questioned his departure, but supporters justified it on medical grounds.

Nawaz’s return after years in exile signals a potential political resurgence. Mushahid emphasized, “He faces a changed landscape but remains one of Pakistan’s most influential figures.” This new chapter underscores his enduring political relevance and ambition.

Comments

See what people are discussing