From crisis to surplus: What is driving Pakistan's rising dollar reserves?

Nation experiencing reversal in balance of payments position with total foreign exchange reserves touching $19.4B in August

Asad Ejaz Butt

Guest Contributor

Asad Ejaz Butt is an economist based in Boston, US. He tweets @asadaijaz.

On February 3, 2023, nearly one year into Shehbaz Sharif’s maiden tenure as prime minister, Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves fell to their lowest since April 2014

At $8.53 billion, total liquid reserves, which include foreign currency assets owned collectively by commercial banks and the State Bank of Pakistan, had declined nearly 68% from their peak of $27.1 billion in April 2014.

The central bank held less than $3 billion of these reserves, covering barely five weeks of imports.

While it averted default, economists predicted that it would take a while for matters to normalize.

In less than 30 months, Pakistan is experiencing a reversal in its balance of payments position with total foreign exchange reserves touching $19.4 billion in August - $14.2 billion of which are U.S. dollar reserves held by the central bank.

But why are Pakistan’s dollar reserves rising? Is this coincidental or indicative of an underlying economic change, and will this sustain?

There are several factors that underlie movements in Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves.

The first is the price of global commodities. Major corrections in the international oil market that was experiencing a supply shortage as a result of maritime shipping and freight disruptions caused by COVID-19, followed by the Russia-Ukraine war eased up Pakistan’s external account.

Continuing on its downward trajectory, Pakistan’s oil import bill witnessed a decrease of 1.19%, dropping to $11.94 billion in the first nine months of FY 25, compared to $12.08 billion during the same period last year.

Strategic correction in global commodity markets

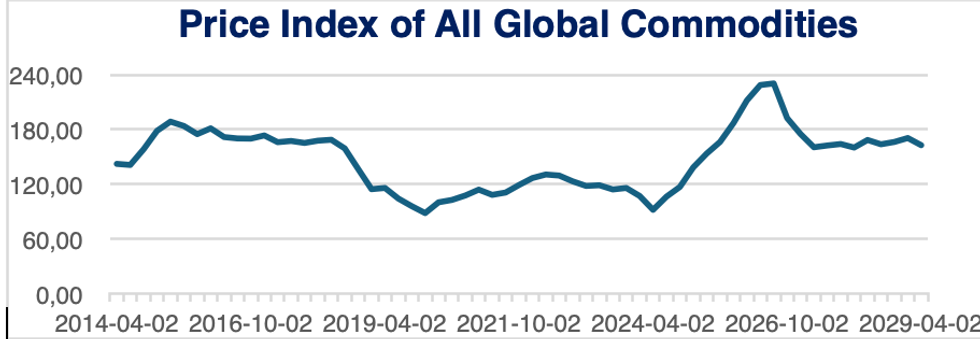

The chart below shows the composite price index for all global commodities.

A downward revision in tariffs in the later part of 2023, followed by a flat line, reflects disinflation in the global commodity market and indicates easing of external liability and payment pressures on net-importing economies.

The chart also shows how prices of these commodities rose sharply starting in April 2022, which is nearly the same time when Pakistan entered a new phase of political instability lasting around 24 months until March 2024.

Political instability added to Pakistan’s economic woes and intensified its external account vulnerabilities, taking it to the brink of default.

For an economy like Pakistan's that relies extremely heavily on imported oil shipments and whose import bills are dominated by energy and petroleum products, any decrease in the international price of these commodities weighs heavily on the country’s ability to arrange dollar cover for future imports and build reserve assets.

While price effects are significant, imports, in this period between the second quarter of FY22 and now, did not only decrease due to lower prices of global commodities, but also to the restrictive import policy adopted by Pakistan’s Finance Ministry.

Restrictive import policy compressed inflow of goods

Pakistan’s imports leveled off due to a strict regulatory control by the government that initially began to tighten the noose in the last quarter of 2022, gradually tapering off controls in 2023, and subsequently after the elections in February 2024.

However, customs duties, tariffs, and non-tariff barriers have remained effective on some product categories despite the recent attack on such protectionist regimes around the world by American President Donald Trump.

The level of imports that existed prior to the economic crunch in FY22 was thus jolted by the dual incidence of disinflation in the global commodity markets, and the government’s policy of import compression.

This took some real pressure off the current account, which is not only breathing by itself now, but perhaps breathing air into an economy surviving on ventilators. Pakistan has recently posted a current account surplus, which is reported to be the country’s first in the last 14 years.

Current account surplus breathing life into forex reserves

Pakistan’s current account returned a surplus of $2.1 billion during FY25, a sharp contrast against a $2.07 billion deficit recorded in FY24. The largest contributor to the surplus was remittances that clocked in at $38.3 billion, reflecting a 27% increase on a yearly basis.

Led principally by prudent import management and stable global commodity prices, this surplus was both timely and surprising, indicating restoration of investor confidence in the economy, positive effects of a few headline economic reforms, and an improving geoeconomic situation.

Apart from import compression and a rising trend in remittances, the reversal in the current account was also helped by a minor tick-up in exports, which while being a sign of a transformational change in the balance of payments dynamics is not significant in itself to cause the turnaround.

Accounting conventions linking current account with reserve assets

Economics is different from accounting in many ways.

One of the salient differences between the two is that economists consider opportunity costs that accountants seem to ignore in their cost estimations.

But nonetheless, the two disciplines converge in their treatment of a nation’s external account.

Economists use double-entry bookkeeping, a central idea in the practice of accounting, to record and manage an economy’s transactions with the rest of the world.

An economy’s current, financial, and capital accounts always sum to zero. These three accounts combined represent a country’s balance of payments position, and the zero-sum game that results from their combination is called the balance of payments accounting identity.

This means that any credit (positive entry) to the current account would be matched by a debit to either the capital or the financial account.

If an economy experiences a current account surplus (credit the current account), it will be used to build up foreign exchange reserves (a debit to the financial account, as this reflects an outflow of capital or a country selling its currency to acquire foreign assets).

The developed nations prefer to use the surplus to lend to poorer nations or make offshore investments (foreign direct investment), both of which form large parts of what economists call a nation’s ‘net foreign wealth’ or its net international investment position (NIPP).

Theoretically, the net foreign wealth has to match with an economy’s current account balance, which is not the case in practice for many economies, including the US, due to the accumulation of debt that prevents the automatic conversion of surpluses (during periods when a surplus occurs) into foreign wealth.

Pakistan is building exports and remittances and compressing imports, all of which have led to a turnaround in its current account and thus, a notable rise in foreign exchange reserves.

These macroeconomic dynamics will continue if this surplus lasts.

*Asad Ejaz Butt is an economist based in Boston, US. He tweets @asadaijaz.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Nukta.

Comments

See what people are discussing