Breaking down Pakistan’s new PECA law: A tool to suppress dissent?

With PECA amendments, the government now decides what is ‘fake news’—and who gets punished for sharing it

Zain Ul Abideen

Senior Producer

Zain Ul Abideen is an experienced digital journalist with over 12 years in the media industry, having held key editorial positions at top news organizations in Pakistan.

PECA amendments expand government control over digital speech

Authorities can now censor content without oversight

Multiple state-controlled bodies will enforce the law

Imagine this scenario: You manage a Facebook page where political discussions take place. A debate unfolds, and tensions rise. Amid the heated exchange, you might not even realize that, under Pakistan’s newly amended Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), you have already committed an offense.

The recent amendments to PECA have fundamentally reshaped the country’s digital landscape, expanding the scope of what constitutes a crime online.

Many of these measures were already in practice, but they lacked solid legal footing and were often challenged in court. Now, with these revisions, the government has ensured that such actions cannot be contested legally.

A legal cover for censorship?

One of the most significant changes is the introduction of “aspersions” as a criminal offense. The law defines it as “spreading false and harmful information that damages the reputation of a person.” This vague wording allows authorities to silence criticism by labeling it as reputational harm. Whether it's a journalist uncovering corruption or an activist questioning state policies, they now risk legal action under PECA.

Another major change is in the definition of a “person.” Previously, PECA primarily targeted individuals, but under the amended law, corporate entities, state institutions, and organizations are also protected. This means that media outlets, watchdog organizations, and even social media users commenting on institutions like the judiciary, military, or parliament could face legal consequences.

The amendments also broaden the definition of a complainant. Previously, legal challenges were often successful because complaints were typically filed by state institutions, making them easier to contest. Now, any individual who believes they have been harmed by online content can file a complaint. This opens the door for politically motivated cases, harassment of dissenting voices, and the weaponization of cybercrime laws against activists and journalists.

The rise of a state-controlled digital regime

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of the law is the establishment of the Social Media Protection and Regulatory Authority (SMPRA). This new body will have the power to:

- Regulate and block social media platforms that fail to comply with government directives.

- Monitor and remove content deemed “offensive” or against the state’s interests.

- Fine or penalize individuals and platforms for violating its regulations.

The authority will be bureaucrat-heavy, with members including the federal interior secretary, the heads of PEMRA and PTA, and other government appointees. This ensures that all decisions on digital censorship will align with government policies.

Adding to this centralized control, the law establishes a Social Media Complaints Council and a Social Media Protection Tribunal. These bodies will handle complaints related to “fake news” and online offenses, with judges and officials picked by the government. The tribunal, headed by a person “who has been or is qualified to be a judge of the High Court,” will have the power to impose penalties, including prison sentences.

The criminalization of digital speech

Under the new amendments, spreading “fake news” can lead to imprisonment of up to three years and a fine of PKR 2 million. But who defines what is “fake news”? The federal government. This effectively means that any narrative contradicting the official state line could be criminalized.

The law also targets social media platforms directly. If a platform refuses to comply with government censorship requests, it can be blocked. The law states:

"The Authority shall have the power to issue directions to a social media platform for removal or blocking of online content."

This applies to content that:

- “is against the ideology of Pakistan,”

- “incites public disorder,”

- “contains aspersions against members of the judiciary, armed forces, or parliament,”

- “promotes or encourages terrorism,”

- or is “known to be fake or false.”

These sweeping definitions provide a legal pretext for shutting down critical voices, particularly those speaking against the government, military, or judiciary.

‘PECA designed to silence free speech’

Barrister Ali Tahir, in conversation with Nukta, points out that PECA has long been a problematic piece of legislation, granting excessive powers to the FIA.

He explains that before PECA was introduced in 2016, various laws governed cyber offenses—cyber harassment was covered under Pakistan’s Penal Code, while cyber fraud fell under the Electronic Transactions Ordinance. However, PECA centralized all these laws, giving the FIA sweeping authority over online speech.

“That has been the problem with PECA that it has been used to target journalists as well as anyone who wishes to talk freely.”

Tahir cites the case of Azam Swati, who was arrested after tweeting about the former army chief Qamar Javed Bajwa. Swati faced over 100 FIRs across Pakistan, with the Sindh High Court dismissing more than 30 of them in one order. This case, he argues, illustrates how PECA is abused to suppress political dissent.

One of the biggest concerns with PECA, according to Tahir, is the vague language used in defining offenses like “fake news” or “false news.”

“For example, if I say Pakistan’s flag is not green but yellow or blue, that would be considered fake news. These provisions have been left intentionally vague, so that anyone can be picked up at any time and jailed.”

Beyond the ambiguity, PECA introduces a chilling effect on free speech. Tahir highlights that the law establishes four different regulatory bodies:

1.The Social Media Protection and Regulatory Authority

2.The National Cybercrime Investigation Authority

3.The Social Media Complaints Council

4.The Social Media Protection Tribunal

“Once these four authorities start building cases against you, you’ll think twice before saying anything. If one authority lets you go, the second will catch you, and if the second lets you go, the third will get you.”

Another troubling aspect is content removal. Under PECA, authorities can block or remove content without notice.

“For example, if this article published in Nukta is deemed objectionable, they can block it without warning. If you want to challenge it, you must go to the tribunal, where the majority of members are appointed by the government, and only one is a judicial officer.”

Even worse, the right to appeal in the High Court has been removed. The only option left is an appeal in the Supreme Court, making it even harder for people to fight back.

Tahir argues that the real intent of the law is not to curb fake news but to criminalize criticism against the government and military.

“Previously, when they arrested people for social media posts, they had no legal justification. The person would go to the High Court, appeal, and sometimes the government had to back off. Now, PECA gives them complete legal cover.”

One of the most absurd aspects of the law, according to Tahir, is the composition of the Social Media Tribunal.

“They’ve put a software engineer and a journalist in the tribunal. But you know very well that anybody can be called a journalist. If the government wants to appoint someone, they’ll simply call him a journalist. That journalist might as well be Atta Tarar [Pakistan’s information minister].”

Tahir warns that PECA will force social media platforms to enlist with the government.

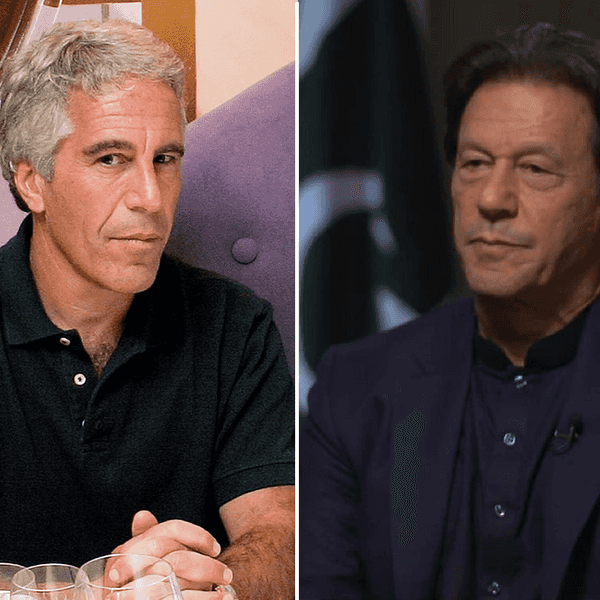

“For example, the government could say that Nukta is a social media platform and must register. If you’re required to enlist and the government controls whether you can operate, will you still have the same freedom? No. Your freedom will be like broadcast media—where even Imran Khan cannot be named, only referred to as ‘PTI founder.’”

“The aim of this bill is nothing else but to control digital media. And that is why it should be opposed.”

What's the 'real' objective?

In conclusion, this legislation appears to be not about tackling cybercrime but about controlling digital spaces that remain outside the government’s grip. Pakistan’s mainstream media, to an extent, is already under state control, and now, the government is moving to dominate social and digital media, the last refuge for independent journalism and activism.

By centralizing authority over online speech and criminalizing dissent, PECA sets the stage for unprecedented digital repression. The internet in Pakistan is at risk of becoming a state-monitored echo chamber where only sanctioned narratives are allowed to exist.

For journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens, the message is clear: speak at your own peril.

Comments

See what people are discussing