Pakistan ranks last in South Asia on literacy, report shows

Only 63% of population can read and write

Business Desk

The Business Desk tracks economic trends, market movements, and business developments, offering analysis of both local and global financial news.

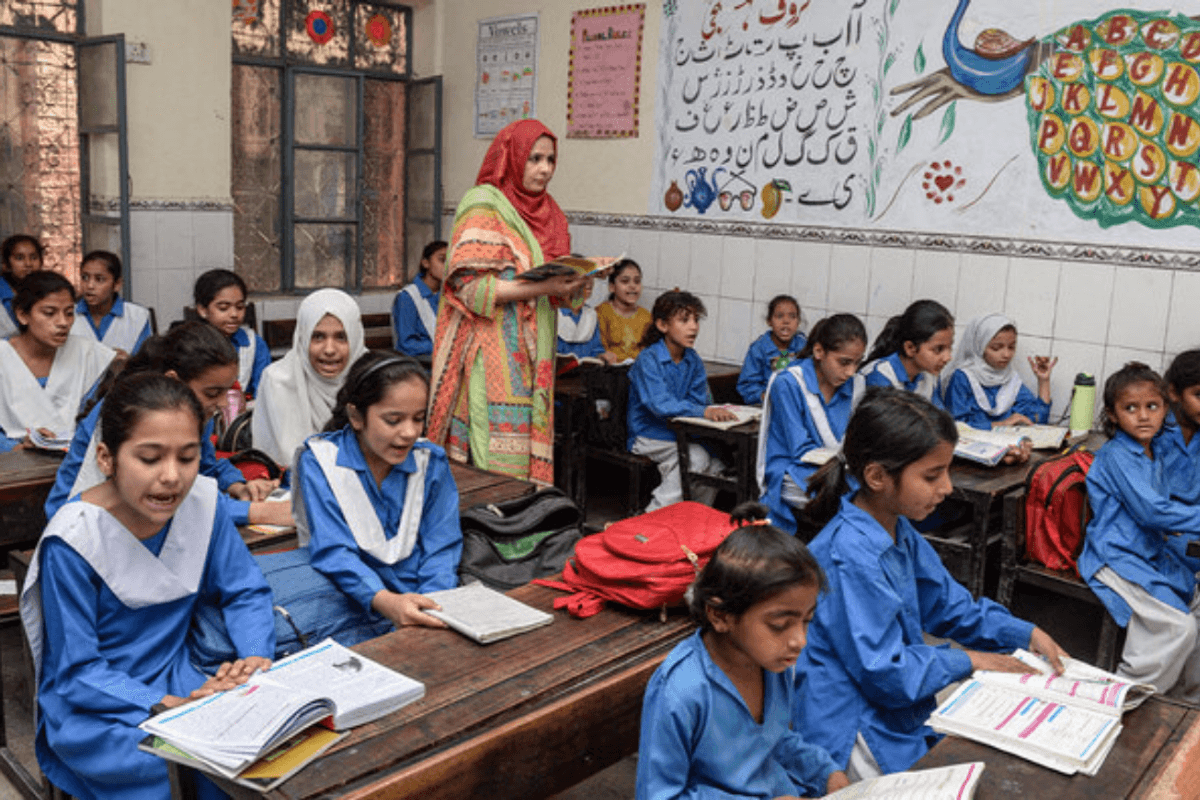

In this photograph taken on May 24, 2024, students attend their class at a school in Lahore, Pakistan

AFP/File

Pakistan continues to rank last in South Asia in literacy, with only 63% of its population able to read and write, underscoring what analysts describe as a sustained policy failure rather than a lack of resources or legal commitments.

A review report released by the Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN), citing data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics and the World Bank, shows that literacy has increased by just 3% since 2018-19, a pace experts say is alarmingly slow for a country of more than 240 million people.

The contrast with regional peers is stark. Maldives leads South Asia with a literacy rate of 98%, followed by Sri Lanka at 93%. India stands at 87%, while Bangladesh reports 79%.

The regional average is 78%, 15 points higher than Pakistan.

The report highlights deep gender and provincial inequalities. Male literacy stands at 73%, while female literacy remains at 54%, reflecting what rights groups call the systematic exclusion of women from education.

Punjab reports the highest literacy rate at 68%, while Balochistan remains the lowest at 49%, pointing to persistent regional neglect.

While youth literacy is reported at 77%, adult literacy lags at 60%, suggesting decades of missed opportunities and ineffective adult education programs.

FAFEN noted that under Article 25-A of Pakistan’s Constitution, the state is legally bound to provide free and compulsory education. Pakistan is also a signatory to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which commit countries to ensuring inclusive and quality education by 2030.

Education analysts argue that the data exposes a widening gap between policy rhetoric and on-ground reality. “The problem is no longer access alone, but weak governance, inconsistent funding, and a lack of political urgency,” an analyst said.

Chronic underinvestment in public schools, poor teacher accountability, and security and infrastructure gaps in underserved regions have collectively stalled progress.

Experts warn that without urgent structural reforms, Pakistan risks locking another generation into low skills and limited economic mobility.

Comments

See what people are discussing