In Pakistan, women shoulder the heaviest burden of climate change

Despite leading 67% of Pakistan’s agricultural workforce, women remain largely invisible in climate policies and gender equality ranks

Asma Kundi

Producer, Islamabad

Asma Kundi is a multimedia broadcast journalist with an experience of almost 15 years. Served national and international media industry as reporter, producer and news editor.

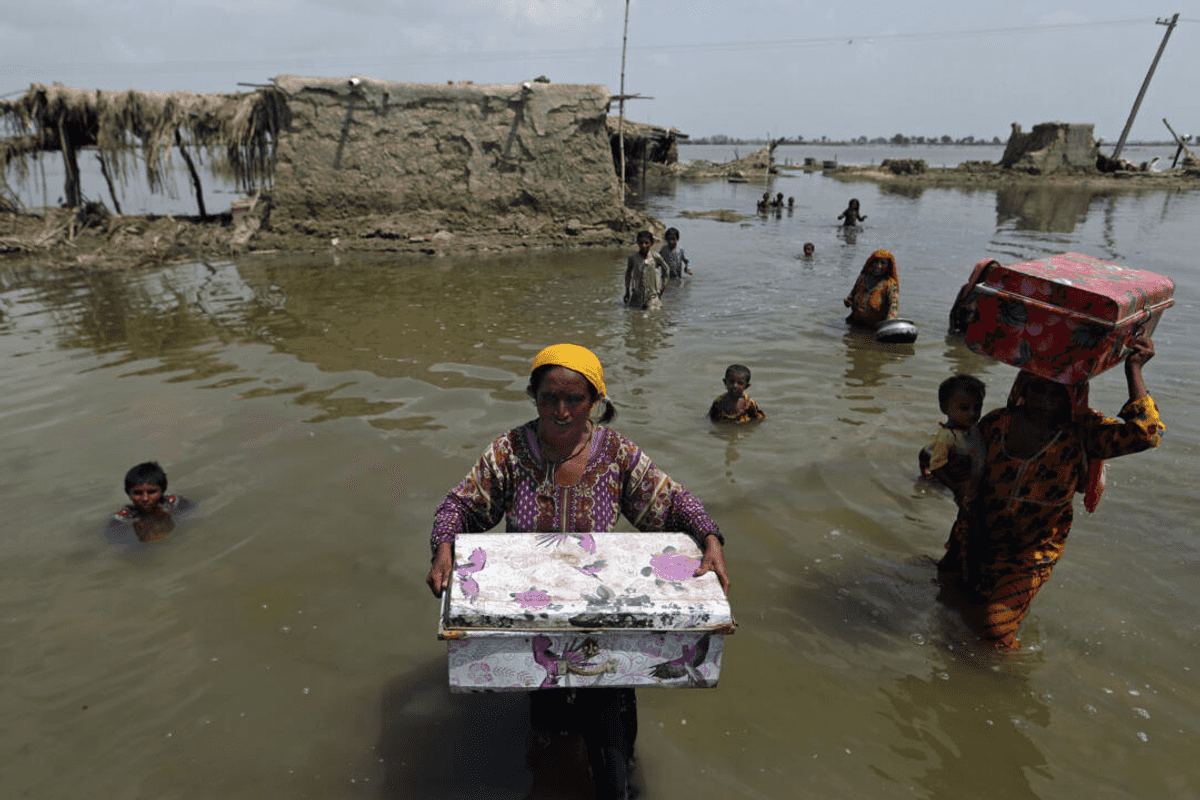

Women carry belongings from their flooded home after monsoon rains in Sindh’s Qambar Shahdadkot district.

AFP/File

When climate disasters strike Pakistan, it is women who bear the brunt - carrying children through floodwaters, tending to parched fields during droughts, and managing households with few resources.

Despite powering over 67% of the country’s agricultural workforce, they remain largely invisible in the very policies meant to protect them. Ranked last out of 148 countries for gender equality, Pakistani women confront the climate crisis with minimal recognition, support, or voice.

Pakistan is among the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations, where floods erase homes, heatwaves suffocate populations, and barren fields deepen hunger.

In these crises, women carry the heaviest burdens: managing relief camps, caring for children and the elderly, and securing basic necessities, often without privacy or safety. According to UN data, women make up the majority of displaced populations and shoulder nearly 80% of caregiving responsibilities, yet their struggles remain absent from policy debates.

Floods, droughts and gender inequality

The 2022 floods exposed these inequalities with stark clarity. Affecting 33 million people, the catastrophe hit women hardest, who constitute more than two-thirds of Pakistan’s agricultural workforce - a sector directly tied to water availability.

Much of their labor is informal, leaving them excluded from social protections when disasters strike. Without access to land ownership, credit, or income control, women are left defenseless when crops fail. The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2025 ranks Pakistan last, with a score of just 56.7%, reflecting the systemic sidelining of women’s needs in both policy and practice.

Finance and data gaps further exacerbate the problem. The World Bank estimates Pakistan requires $7-14 billion annually for climate adaptation, yet only about 1% of global funding for developing nations reaches women-focused programs, according to UN Women.

Gender-disaggregated data covers only 57% of the population, while 60% of national institutions suffer from budget cuts. When women’s realities are missing from the numbers, they disappear from policy solutions.

Steps forward, but gaps remain

There are small signs of progress. UNDP’s 2025 report highlights the Climate Gender Action Plan (2022) and the 2025–26 budget as milestones, marking the first time Pakistan has tracked both climate and gender expenditures.

Initiatives like vocational training and climate-smart agriculture have helped nearly 10,000 women rebuild livelihoods in flood-hit areas. Yet these programs cover only a fraction of the need - gender-tagged projects account for a mere 0.2% of the Public Sector Development Program.

Other sectors tell a similar story. Amnesty International’s 2024 report notes that health spending remains at just 1% of GDP, leaving weak systems unable to capture women’s specific needs.

Vulnerable groups, including elderly women and transgender communities, face amplified risks, often excluded from relief and recovery efforts.

Women as agents of change

“Pakistan’s climate policies are not gender-responsive,” said Dr. Zainab, founder of Saheli, a youth- and women-led think tank. “Pre-, during-, and post-disaster planning is not women-led. That’s why women remain invisible in the very policies meant to protect them.”

She has witnessed the same cycle repeat every monsoon: aid arrives, relief efforts ramp up, but once the waters recede, attention fades until the next disaster.

To address this, Saheli has launched Feminist Future Labs in various cities - spaces where communities identify challenges and co-create long-term solutions.

“We cannot always look outside for answers. This is our problem, and communities must shape the solutions collectively,” she said.

Sarwat Jahan, Director of Programs at PODA Pakistan, stressed the need for psychosocial support for women affected by floods. “Only then can they contribute productively.

Moving beyond seeing women as victims requires systemic changes in governance, financing, capacity-building, and cultural norms. Women’s representation in decision-making at every level is essential.”

Yasmeen, an advocate working with rural women, emphasized the need for compensation for lost livestock and crops, and inclusion of rural women, indigenous groups, youth, and women with disabilities in decision-making. Urban women often access opportunities, but rural women remain largely left behind. Gender-responsive financing, from both government and private sectors, is crucial for equitable recovery.

The evidence is clear: Pakistan’s climate policies acknowledge the importance of gender inclusion, but without adequate resources, reliable data, and genuine representation, these promises remain hollow. Until systemic gaps are addressed, women will continue to carry the heaviest burden of a warming world, standing on the frontlines of survival while remaining invisible in policy.

Comments

See what people are discussing