Khan's civil disobedience: A revolution in the making or a risky rerun?

Amid economic strain and political uncertainty, PTI's bold strategy faces history’s harsh lessons

Javed Hussain

Correspondent

I have almost 20 years of experience in print, radio, and TV media. I started my career with "Daily Jang" after which I got the opportunity to work in FM 103, Radio Pakistan, News One, Ab Tak News, Dawn News TV, Dunya News, 92 News and regional channels Rohi TV, Apna Channel and Sach TV where I worked and gained experience in different areas of all three mediums. My journey from reporting to news anchor in these organisations was excellent. Now, I am working as a correspondent with Nukta in Islamabad, where I get the opportunity of in-depth journalism and storytelling while I am now covering parliamentary affairs, politics, and technology.

Khan has called on overseas Pakistanis to stop sending remittances as part of his movement

This is the second time Khan has called for the movement in his political career

Internationally, the most famous use of the movement was by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930

Civil disobedience movements in Pakistan have historically been long on rhetoric but short on results. Former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s latest call for such a movement raises questions about its potential impact amid heightened political polarization and economic instability.

The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) founder, currently in jail, has set a Dec. 14 deadline for the government to meet two key demands: release under-trial PTI political prisoners and establish a judicial commission to investigate the events of May 9 and Nov. 26. If the demands are not met, Khan has vowed to launch a nationwide civil disobedience movement.

This is the second time Khan has resorted to civil disobedience in his political career. While the tactic can be a powerful tool for resistance, its success often depends on strong public support and consistent leadership—both of which have proven elusive in Pakistan’s previous attempts.

What is civil disobedience?

Civil disobedience, a form of nonviolent resistance, typically involves refusing to comply with certain laws or pay taxes to protest government actions.

Internationally, it has been most famously employed by Mahatma Gandhi, whose Salt March in 1930 was a pivotal moment in India’s struggle against British colonial rule.

In Pakistan, however, the concept remains largely theoretical. Political parties have occasionally threatened to launch such movements, but these announcements rarely materialize into organized action.

“Civil disobedience movements require not just a call to action but mass mobilization, clear objectives, and steadfast leadership,” senior journalist Iftikhar Hussain Shirazi told Nukta. “In Pakistan, these elements have often been lacking, leading to failures.”

Khan’s 2014 attempt

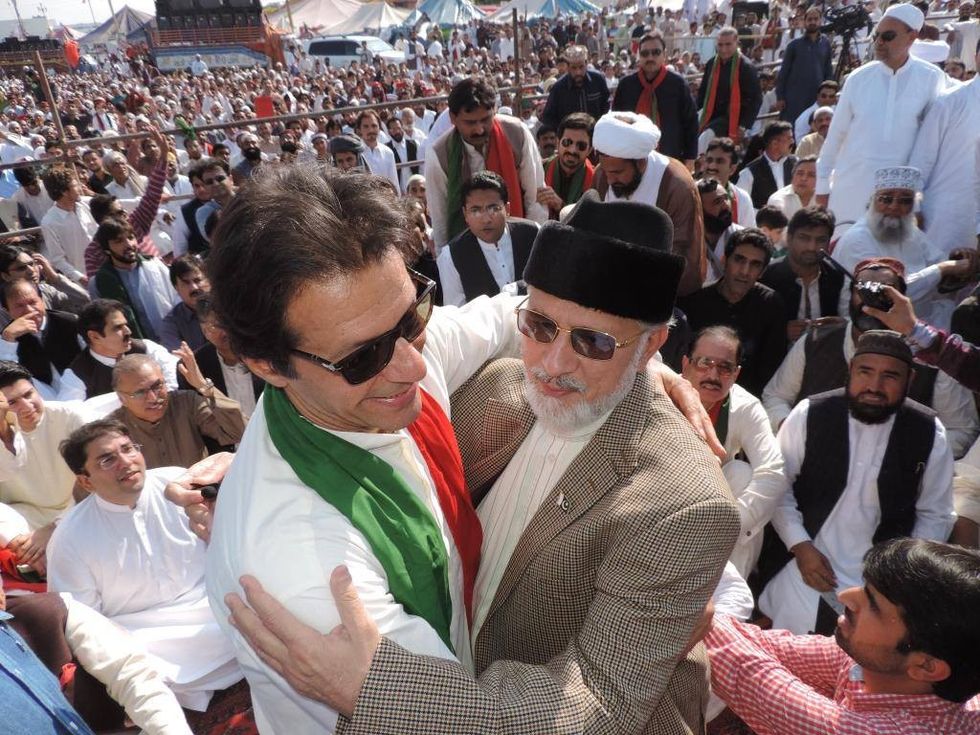

Imran Khan previously called for civil disobedience during his party’s 2014 sit-in against alleged electoral fraud.

At the time, he urged citizens to stop paying utility bills and taxes. However, the movement faltered when it was revealed that Khan himself had paid his electricity bills, undermining his credibility.

Senior journalist Javed Siddique noted “the failure of the 2014 campaign was rooted in inconsistency and a lack of public buy-in. People didn’t see the leadership taking the same risks they were asked to take.”

New strategy, higher stakes

PTI’s strategy this time is more expansive. Alongside domestic actions, Imran Khan has called on overseas Pakistanis—a demographic crucial to the country’s economy—to stop sending remittances as part of his movement.

With remittances from overseas workers contributing over $3 billion monthly, PTI aims to restrict this financial inflow.

Additionally, PTI has formed a negotiation team, including prominent figures like Omar Ayub Khan, Ali Amin Gandapur and Salman Akram Raja, to engage with stakeholders.

The party has also hinted at intensifying actions in the movement’s second phase, though specifics remain undisclosed.

“The involvement of overseas Pakistanis could potentially amplify the impact,” said economist Dr. Shabbar Zaidi. “However, it’s a double-edged sword. If remittances decline significantly, it could further destabilize Pakistan’s already fragile economy," he added.

A political gamble

Imran Khan’s announcement comes at a time of mounting challenges for PTI. Following widespread crackdowns on the party after the May 9 riots and other political tensions, PTI has faced defections and organizational disarray.

However, public sympathy for Khan and his party appears to have grown. In the February 2024 general elections, PTI claimed to have won 180 National Assembly seats, though the official tally was disputed.

“This sympathy could translate into public support for the movement, but it’s a risky bet,” said Shirazi. “If the movement fails, it could weaken PTI’s standing further. If it succeeds, it could reshape Pakistan’s political landscape.”

The role of history

Historically, Pakistan has witnessed few attempts at civil disobedience. The most notable instance was during the secessionist movement led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1971, but this was tied to broader geopolitical and ethnic conflicts.

The closest parallel in terms of political alliances was the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) movement against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. Though not a civil disobedience campaign, the PNA’s efforts demonstrated the power of collective political action.

“Imran Khan’s movement, if it gains momentum, could be the first organized civil disobedience in Pakistan’s history,” Siddique said. “But the challenges are immense, and past failures loom large,” he added.

Public sentiment and challenges

Public anger over recent events, including the treatment of PTI workers during protests, could provide fertile ground for the movement. However, analysts caution that public mobilization remains uncertain.

“People are frustrated with the economic situation and political instability, but translating that frustration into collective action is a different matter,” Zaidi said.

Additionally, the government’s response will be crucial. A heavy-handed crackdown could either suppress the movement or galvanize public support, depending on how events unfold.

Looking ahead

As the December 14 deadline approaches, the stakes for both PTI and the government are high. Imran Khan’s call for civil disobedience could mark a turning point in Pakistan’s political history—or it could become yet another failed chapter in the country’s turbulent democratic journey.

The next few weeks will determine whether this movement can succeed where others have faltered, or whether it will join the list of unfulfilled promises in Pakistan’s political annals.

Comments

See what people are discussing