Pakistan can unlock $4.7B from exports to Bangladesh if barriers fall

The recent visit of Deputy PM Ishaq Dar to Dhaka has sparked fresh momentum in bilateral ties, with six new deals, as talks turn to market access and tariff reform

Nida Gulzar

Research Analyst

A distinguished economist with an M. Phil. in Applied Economics, Nida Gulzar has a strong research record. Nida has worked with the Pakistan Business Council (PBC), Pakistan Banks' Association (PBA), and KTrade, providing useful insights across economic sectors. Nida continues to impact economic debate and policy at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and Nukta. As a Women in Economics (WiE) Initiative mentor, she promotes inclusivity. Nida's eight 'Market Access Series papers help discover favourable market scenarios and export destinations.

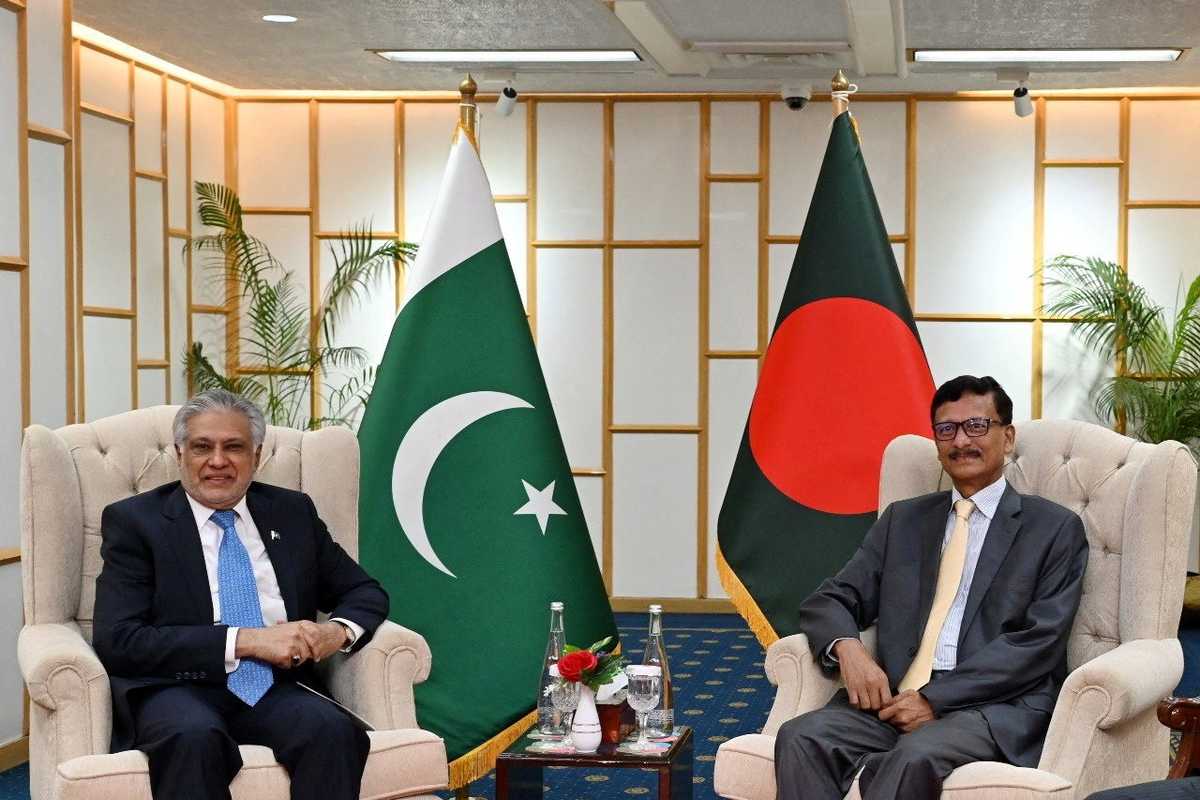

Mohammad Touhid Hossain, Foreign Affairs advisor of Bangladesh's interim government and Ishaq Dar, Pakistan's foreign minister, attend a bilateral meeting in Dhaka, Bangladesh

REUTERS

For two countries that share history and an uneasy political past, Pakistan and Bangladesh trade remarkably little. Their combined commerce is barely a rounding error compared to what each of them does with India or China. Yet this week, as Pakistan’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, Ishaq Dar, toured Dhaka and signed six accords on media, culture, and diplomacy. The real prize was not the ink on paper but the prospect of something far bolder: the revival of long-stalled talks on a free trade agreement (FTA).

The idea of an FTA between Pakistan and Bangladesh was first proposed in 2002. This was further discussed at the 2004 South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) summit by the commerce ministers of both countries. When negotiations began, Bangladesh presented its demand for free access to Pakistan’s markets within one year of the FTA's signing, citing its status as a Least Developed Country (LDC). Bangladesh also insisted on a “negative list approach” in trade negotiations to protect its market. However, the negotiations were never concluded.

Now, with Bangladesh’s graduation from LDC status looming in 2026, the incentive to lock in new markets is stronger than ever.

Trade potential: billions left on the table

Though Pakistan is not currently a big export market for Bangladesh, bilateral trade has consistently favored Pakistan. Exports to Bangladesh, however, have declined from a peak of $947 million in 2011 to $778 million in 2024.

Imports from Bangladesh also nearly halved, falling from $82 million in 2011 to $46 million in 2024. This left Pakistan with a positive balance of $732 million in 2024 — its fourth-highest trade surplus with Bangladesh since 2005. Currently, Pakistan’s exports to Bangladesh are at least 17 times larger than its imports.

Trade flows between the two countries remain highly concentrated: the top ten items account for 95% of Pakistan’s exports. According to ITC Trade Map data, in 2024, cotton dominated the trade, representing 76% of total exports. Other key exports were cement and salt ($53 million or 6.9%), inorganic chemicals ($30 million or 3.9%), and sugar and confectionery ($12 million or 1.6%).

Yet the potential is far greater. Nukta’s analysis shows Pakistan has at least $4.68 billion in untapped export potential in Bangladesh, spanning across textiles, agriculture, foodstuffs, chemicals, base metals, plastics, and cement products.

Textiles could add $700 million in yarn and fabric exports to support Bangladesh’s garment sector.

Agriculture offers openings in onions, fresh produce, spices, and seeds.

Chemicals, plastics, cement, and salt present further scope, with Pakistani salt alone holding an $11 million market opportunity.

On the flip side, Bangladesh could expand exports of man-made fibers, pharmaceuticals, and light engineering goods to Pakistan if tariff and regulatory barriers are eased.

Tariffs and non-tariff barriers still block the way

According to Global Trade Alert data, Pakistan has enacted several trade measures over the past decade that directly impacted Bangladesh. These include tax-based export incentives on textiles and hides (2014–15), the inclusion of brown rice exports under concessional financing (2014), and a range of export incentives for pharmaceuticals and furniture. More controversially, in 2015, the National Tariff Commission imposed anti-dumping duties on hydrogen peroxide (HS 284700) imported from Bangladesh, a measure still in force today and a persistent irritant for Bangladeshi exporters. Other steps, such as duty drawback schemes and concessional financing for Pakistan’s own textile and spinning sectors, while not discriminatory in wording, created asymmetries that disadvantaged Bangladeshi competitors. Together, these interventions underscore how Pakistan’s policy — part liberalizing and part restrictive — has shaped a complex trade environment for Dhaka.

These policies highlight why bilateral trade is skewed. Pakistan maintains a large trade surplus with Bangladesh (exports 17 times higher than imports in 2024). Rather than hurting Pakistan’s exports, these measures reinforce Pakistan’s position as the stronger trading partner while Bangladesh faces persistent barriers in penetrating the Pakistani market.

Bilateral market access: concentrated and uneven

Both countries maintain stiff tariff schedules that constrain trade flows. Bangladesh imposes duties of up to 25% on Pakistani textiles, while Pakistan has enforced anti-dumping duties on hydrogen peroxide, a key Bangladeshi export.

At the harmonized system sectoral level (HS-02 level), Pakistan’s tariffs on Bangladeshi goods range from 2% to 59%, with an average of 7.8%. Of the 99 chapters, 25 face rates of 2 to 4%, 71 face 5 to 59%, and only two — beverages (HS-22) and vehicles (HS-87) — fall in the top 30 to 59% bracket.

In contrast, Bangladesh’s tariffs on Pakistani goods average 9%, with 16 chapters at 0 to 2%, 27 at 3 to 5%, and a ceiling of 25%.

Why an FTA now?

An FTA or Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) between Pakistan and Bangladesh could:

Rationalize tariffs under the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) framework.

Tackle non-tariff barriers (NTBs) through customs cooperation and mutual recognition of standards.

Enable Pakistan to plug into Bangladesh’s global apparel supply chains.

Offer Bangladeshi investors access to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) for routes into western China and Central Asia.

The road ahead

The six agreements signed in Dhaka may be modest in scope, but they have reopened a larger debate. For Pakistan, diversifying exports beyond cotton is an economic necessity. For Bangladesh, securing new markets before LDC graduation is a strategic priority.

Whether the FTA finally materializes depends less on technical negotiations than on political will.

Comments

See what people are discussing