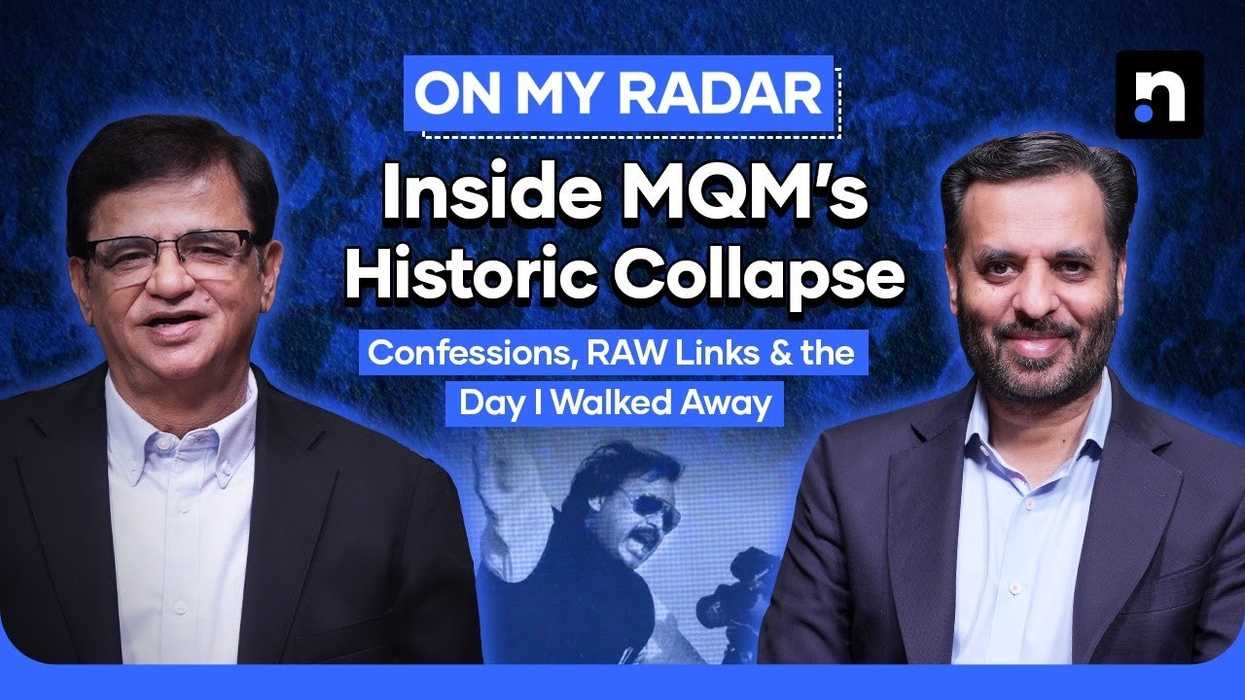

Mustafa Kamal recounts MQM’s rise, cult of Altaf, and clash with the state

In a podcast with Kamran Khan, former Karachi mayor recalls how MQM morphed from a movement for Mohajir rights to a state within a state

News Desk

The News Desk provides timely and factual coverage of national and international events, with an emphasis on accuracy and clarity.

Former Karachi mayor Mustafa Kamal traced the meteoric rise and violent unraveling of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), offering a rare inside view of a party that once controlled the country’s largest city through street power, political deals, and unflinching loyalty to its exiled founder, Altaf Hussain.

“This was around 1985–86. After the Bushra Zaidi incident, riots broke out—and that’s when MQM was actually formed,” Kamal recalled during a podcast with Kamran Khan, referring to the death of a college student that triggered ethnic riots in Karachi.

“By the time the first local elections happened in 1987, we had become unofficial MQM workers.”

Kamal said job ads would openly discriminate against Urdu-speaking candidates, fueling a sense of collective deprivation that the MQM capitalized on.

“When Altaf Hussain stood on the streets and spoke out, it felt like he was speaking directly to us,” he said. “There’s an energy in ethnic and linguistic identity—it pulls you in.”

Early victories

In 1987, MQM secured mayoral offices in Karachi and Hyderabad unopposed. Kamal said these victories gave the Mohajir community a sense of power they had never felt before.

“We saw people from our neighborhoods become councilors, and water and sewerage issues actually started getting resolved,” he said.

By 1988, MQM had entered the Sindh government and received three ministerial portfolios. For the first time, the party was part of the ruling setup.

“There was this spirit of sacrifice,” Kamal said. “If a unit had 17 boys and an employment opportunity came, all 17 would refuse it. It was considered shameful to join MQM for personal gain.”

Slogans like “MQM cannot be bought” adorned Karachi’s walls, reflecting the ideological commitment of its early members.

The cult of Altaf Hussain

Kamal said that loyalty to Altaf Hussain soon crossed into “blind worship”. “We were practically worshipping him,” he admitted. “We even used sticks to make the public follow suit.”

Critics were dismissed as “Jamaatis,” and dissent within the community was violently suppressed. “We acted like lunatics,” Kamal said.

Despite warnings from elders urging MQM to pursue national-level politics, the party remained rooted in Mohajir identity. “We raised our voices against people we’d never dare speak to before. That’s how strong the pull was,” Kamal said.

Alliance with establishment

Kamal alleged that MQM's ties with the country’s powerful military establishment began from day one. “General Hameed Gul, the architect of the opposition alliance, visited Nine Zero. We felt validated,” he said.

Kamal said the alliance was covert but ever-present. “Altaf Hussain maintained an anti-establishment image while consulting them on everything,” he claimed.

The turning point came in 1992, when the military launched Operation Cleanup to dismantle MQM’s militant wing. “We had become a state within a state,” Kamal said. “People would go to unit offices instead of police stations.”

Bloodshed and betrayal

According to Kamal, MQM reached the peak of its power during the alliance with Nawaz Sharif’s federal government and Sindh Chief Minister Jam Sadiq.

“Senior MQM minister Tariq Javed was the de facto CM,” he said.

But this was also the era when corruption and armed violence escalated. Kamal recalled intense ethnic clashes, including the Hyderabad massacre and the December 14 Qasba-Aligarh attack that killed 350 people.

“It was during this time that Altaf Hussain famously said: ‘Sell your TV and VCR, buy weapons,’” Kamal said.

1992 operation

The crackdown that began in June 1992 sent MQM underground. Kamal said entire neighborhoods became battlefields overnight.

“We were told, ‘Hide wherever you can. Don’t let sunlight touch you,’” he said. “Eighteen MQM workers were killed on the first day.”

MQM responded by building a camouflaged communications network using pagers and secret phone lines. Altaf Hussain fled the country, and top leaders like Dr. Imran Farooq went into hiding for years.

“People didn’t turn them in. That’s how much support we still had,” Kamal said.

In the 1993 elections, the establishment allegedly tried to push MQM-Haqiqi, a breakaway faction. But MQM swept the polls again, winning 28 seats.

“They had the guns, but people stamped the kite symbol in defiance,” Kamal said.

Repression and resurgence

Even after the electoral victory, the crackdown continued under Benazir Bhutto’s government. Kamal said 24 of MQM’s 28 lawmakers were jailed in Adiala prison.

“Extrajudicial killings became routine,” he said. “Young men turned into neighborhood sentinels—whatever you say now, they were heroes back then.”

According to Kamal, none of it reduced MQM’s grassroots support. “In their hatred for all opposing forces, people kept gravitating back to MQM,” he said.

When Nawaz Sharif returned to power, violence flared again. “Governor’s Rule was imposed, and then Hakeem Saeed was assassinated,” Kamal recalled.

A legacy of blood and loyalty

By the time MQM returned to power in the late ’90s, Kamal said, it came back with “seven years of resistance, bitterness, and pent-up anger.”

In hindsight, he believes the 1992 operation may have been inevitable. “If MQM had been left alone for five more years, it would’ve collapsed on its own,” Kamal said.

But it didn’t. Instead, it became a symbol of both empowerment and extremism.

“We paid the price,” Kamal said. “And so did everyone else.”

Comments

See what people are discussing