Why Pakistan's political party bans rarely stick long-term

At least six major political parties and many more political groups have been prohibited since independence in 1947

Umer Zaib

Senior Producer

Umer Zaib is a Karachi-based journalist and good Samaritan with five years of experience at Pakistan's leading news publications.

Constitutional process requires Supreme Court adjudication of all bans

Banned parties typically re-emerge under different names or through talks

TLP remained election-eligible even while technically banned in 2021

Pakistan's federal cabinet approved banning a far-right religious party for the second time in four years, part of a decades-long pattern in which successive governments have outlawed political organizations—often with limited long-term success.

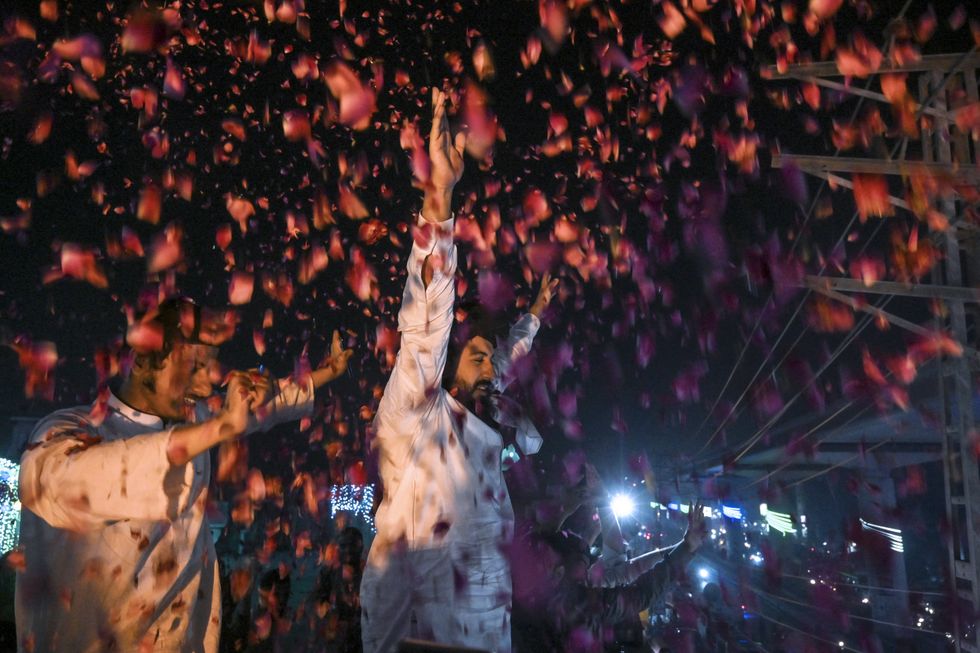

The cabinet decision followed a meeting chaired by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif on Thursday, where law enforcement agencies briefed officials on Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP)'s recent violent protests in Lahore and Muridke that left police officers dead and hundreds injured.

TLP was previously banned in April 2021 after similar violent protests but the ban was lifted just seven months later following continued demonstrations and negotiations. The party remained eligible to contest elections even while technically proscribed, as the Election Commission never delisted it.

Past bans

Pakistan has banned at least six major political organizations since independence, though most prohibitions have proven temporary. The Communist Party of Pakistan became the first banned party in 1954, accused of attempting to overthrow Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan's government.

Jamaat-e-Islami was banned in Pakistan in 1964 by President Ayub Khan’s military regime for opposing martial law and being declared an “unlawful association” accused of subversion and foreign links. The ban was short-lived.

General Yahya Khan banned the Awami League in March 1971, calling its leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's movement "an act of treason," a decision that contributed to Bangladesh's independence.

The National Awami Party faced bans thrice, in 1958, 1971 and 1975, before re-emerging as the Awami National Party (ANP), which is active to date. The Sindhi nationalist party Jeay Sindh Qaumi Mahaz-Aresar (JSQM-A) was banned in 2020 over alleged links to militant groups.

Many religious organizations, such as Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan and Islamic Tehreek Pakistan, have also been banned at various times while describing themselves as political parties. However, these groups are typically classified as sectarian or militant outfits rather than formal electoral parties, which is why they are not counted among the six major political bans. More recently, the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM), a rights group advocating for ethnic Pashtuns, was banned in October 2024.

Legal mechanism

There are two legal pathways for banning a political party in Pakistan. Islamabad-based lawyer Neha Touseef notes that Article 17(2) grants citizens the right to form political parties, but restrictions “must be imposed by law.” She emphasizes that any such law must require the government to refer a ban to the Supreme Court within fifteen days, whose decision is final — meaning, as she puts it, “the federal government’s decision alone isn’t final.”

However, governments have routinely bypassed this constitutional safeguard by instead invoking Section 11B of the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997, which allows immediate executive bans without prior judicial authorization. Touseef says Section 11B “gives the federal government power to impose a ban on an organization on an ex parte basis.” This, she explains, effectively sidelines the Supreme Court’s oversight envisioned under Article 17(2).

Every recent political party ban - TLP (2021), JSQM-A (2020), and PTM (2024) - used the ATA route, avoiding Supreme Court oversight entirely. This explains why banned parties remain on electoral rolls and continue operating: the constitutional process designed to legitimize bans is skipped.

Touseef notes such use of the ATA “sidesteps what the Constitution clearly requires,” that any restriction must be grounded in a law providing for judicial review.

Karachi-based lawyer Ali Tahir notes that while sitting legislators should theoretically be disqualified and party bank accounts frozen, “the real issue for any major political party is that you take away its representation from the assembly,” a consequence that “rarely materializes in practice.”

Are bans effective?

Most government attempts to permanently ban political parties have fizzled out, as proscribed organizations typically rebrand under new names, operate underground through affiliated groups, or leverage street protests to force reversals.

The Communist Party of Pakistan, outlawed in 1954, simply went underground and continued operating through its student wing, the Democratic Students Federation, until that too was banned. The National Awami Party's 1975 prohibition, despite Supreme Court endorsement, merely prompted the party to rebrand as the National Democratic Party and resume political activity, which later merged with others to form the ANP in 1986.

Similarly, the Awami League's ban in 1971, despite disqualifying 76 of its 160 elected members as traitors, failed to extinguish the party's political influence. It went on to lead Bangladesh after independence and has governed the country for much of its history.

Even militant groups have found ways to circumvent bans. Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, banned in 2002, rebranded as Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat to continue operating. This further illustrates that if proscribed militants can return under new names, party bans, which face far fewer constraints, are unlikely to be fully effective.

Even military dictator General Pervez Musharraf, despite having the power to enact constitutional amendments unilaterally, avoided outright party bans. According to Tahir, Musharraf "did not enact outright bans because, as history has shown, they are never successful." Instead, Musharraf used targeted restrictions, such as the Political Parties Order 2002, which barred convicted persons from heading parties, to sideline rivals like Benazir Bhutto without formally banning their parties.

Touseef adds that even if a party is banned, “individuals can still run for elections independently,” since disqualification depends on personal conduct under Articles 62 and 63. That legal gap also contributes to why bans rarely erase political movements in Pakistan.

The TLP's earlier ban in 2021 proved particularly illustrative: after being banned in April 2021, the party not only secured the ban's reversal within seven months through sustained street protests but remained on the electoral rolls throughout. It eventually emerged as the country's fourth largest political party in the 2024 general elections, receiving more than two and a half million votes countrywide.

Comments

See what people are discussing