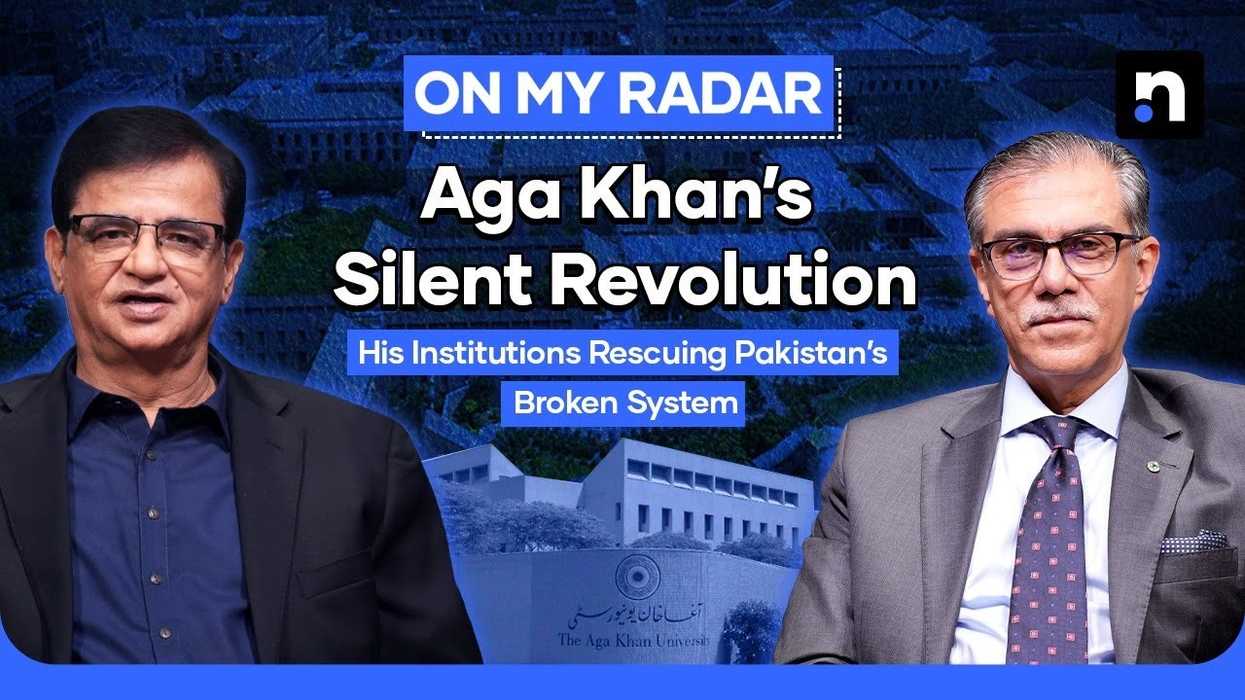

How the Aga Khan Network is transforming healthcare and education in Pakistan

With donor support, Aga Khan institutions offer a rare model for sustainable, equitable health and education in Pakistan, says Kamran Khan

News Desk

The News Desk provides timely and factual coverage of national and international events, with an emphasis on accuracy and clarity.

Education and healthcare are the twin foundations on which every successful nation stands. In Pakistan, however, both sectors have long failed to meet public expectations -- burdened by neglect, inefficiency, and underinvestment.

In response, the private sector has stepped in to fill the gap. Leading this effort for over 65 years is the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), whose investments in education and health have quietly but profoundly impacted millions of Pakistanis.

In a latest episode of On My Radar, Kamran Khan spotlighted the contributions of the Aga Khan institutions. Under the umbrella of Aga Khan Educational Services, Pakistan currently hosts more than 150 schools and higher secondary institutes, serving over 50,000 students with an internationally recognized curriculum.

At the same time, the Aga Khan University (AKU) provides a wide spectrum of healthcare education with 3,700 students currently enrolled in medicine, dentistry, nursing, technical health sciences, diplomas, and postgraduate specializations.

The flagship Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) in Karachi is the country’s largest private hospital, boasting 700 beds and treating 1.2 million patients annually through its emergency, outpatient, and specialty services. Patients from all across Pakistan are referred here for complex cardiac, cancer, neurological, and maternity care. Its expansive network includes internationally certified diagnostic labs, clinics, and collection points.

Across Pakistan, over 14,000 doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals are employed within the Aga Khan Health Network, many of whom are also engaged in research and training.

Dozens of centers operate in remote areas like Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral, while districts in Punjab and Sindh benefit from its primary health and maternal-child care units. Globally, AKDN runs 14 hospitals and 375 health centers in Central Asia, South Asia, and East Africa. Recognized by WHO and UNICEF, these efforts have made the network one of Pakistan’s most credible and valuable private-sector partners.

Introducing his special guest, Kamran Khan welcomed Dr. Sulaiman Shahabuddin, President of Aga Khan University.

Born in Karachi and an IBA MBA graduate, Dr. Shahabuddin has served the AKDN for nearly 35 years -- including a tenure as Regional CEO for East Africa -- before becoming President in 2021. For his service, he was awarded the Sitara-i-Imtiaz by the Government of Pakistan.

A breakthrough in education: Teacher licensing in Sindh

Dr. Shahabuddin celebrated a landmark achievement in education. After two years of collaboration between Aga Khan University’s Institute for Educational Development and NGOs like Shehzad Roy’s Life Trust, the Sindh government passed legislation introducing mandatory teacher licensing.

“These are the individuals we entrust with our future -- our children’s education, training, and character-building,” he said. “If these teachers don’t hold licenses, if there’s no verification of their capability, what are we doing?”

He expressed deep gratitude to the Sindh government and urged Punjab, Balochistan, and KP to follow suit. Licensing, he said, would elevate professional standards and empower teachers to teach critical thinking -- an essential skill for modern learners.

Primary healthcare: The missing link in Pakistan’s health system

Turning to a national crisis, Dr. Shahabuddin addressed the systemic failure of primary healthcare in Pakistan.

“The system is being misused. If you live in a village or town, your first point of contact should be a government-run health center. But when these facilities lack medicines, doctors, or infrastructure, people are forced to rush to high-level hospitals.”

This overburdens tertiary hospitals, wastes resources, and ignores basic care needs. He said many countries have strengthened their primary systems, but Pakistan continues to lag.

“Today, even for something as minor as a headache, people go straight to Aga Khan Hospital, Jinnah Hospital, or Liaquat National. These conditions should be treated locally. But with no referral system in place, people bypass basic care.”

He pointed to global models -- the UK, Canada, and especially Cuba, where 70% of healthcare needs are met within the community.

“People don’t decide on their own where to go. There’s a structured referral system. That’s what Pakistan needs to build.”

Losing our nurses and doctors: A growing crisis

Dr. Shahabuddin warned of an exodus of healthcare professionals from Pakistan.

“We’re losing 30 to 40 percent of our nurses -- a very high number. The West has always been attractive, but now Gulf countries are also hiring.”

He explained that Gulf recruiters specifically seek staff from accredited joint commission, like AKU.

“Recruiters are at our doors. We lose about a third of our nurses. Many postgrad doctors stay, especially specialists. But undergraduates leave for residencies and fellowships abroad—and very few return.”

He said AKU has had some success in bringing doctors back, but it remains a challenge.

“We must create an environment that convinces them to stay -- competitive salaries, professional support, and better living conditions. Without these, we will keep losing them.”

No profit motive: Serving 77% of patients, supporting 80% of students

Dispelling myths, Dr. Shahabuddin clarified that AKU and its health and education units are not-for-profit institutions.

“These are not commercial enterprises. Even if a surplus is generated, it’s entirely reinvested into Pakistan -- whether through expanded capacity or better technology.”

“In most cases, there’s no surplus -- just losses that must be covered. Prince Aga Khan still provides millions of dollars annually to support the university.”

He explained that 77-78% of hospital patients -- around 1 million annually -- receive financial assistance. Likewise, nearly 80% of students receive aid in the form of scholarships or student loans.

“We’re not generating profits to send to Paris or Prince Aga Khan. In fact, not a single rupee leaves Pakistan -- millions of dollars actually come into the country every year.”

Much of this support comes from the Ismaili community, but now corporate donors and individuals in Pakistan are stepping up too. He also highlighted support from international partners like the French Development Agency and German Development Agency, which offer concessional loans and grants.

“All the progress you see today -- new equipment, new hospitals, expanded services -- is possible only because of donor support and soft funding.”

Expansion plans: New university hospitals in Islamabad, Lahore and Peshawar

Looking ahead, Dr. Shahabuddin revealed plans to expand AKU’s hospital network into major Pakistani cities.

“We are now refocusing efforts to establish full university hospitals in Islamabad, Lahore, Peshawar, and more. Feasibility studies are complete. Punjab and other provincial governments are supportive.”

This expansion builds on AKU’s presence in 130 cities across Pakistan, through clinics and health centers. The goal is to provide international-standard care nationwide -- not just in Karachi.

Merit over influence: No calls, no favors

Closing on a principled note, Dr. Shahabuddin underscored AKU’s strict commitment to meritocracy.

“When admissions open, I get calls asking for favors. My answer is always no. Even the chairman of the board can’t help. I doubt even Prince Aga Khan would interfere -- it’s a merit-only process.”

He described similar pressure in hospital settings:

“People ask me to reduce charges or prioritize wealthy patients. But both Prince Aga Khan and I believe no one should get better treatment just because they can afford it.”

“If you want a private room, sure. But the standard of care must be equal, whether you're in general ward or VIP.”

He acknowledged the existence of a protocol department:

“If someone makes a request, we offer protocol -- but without extra charges. It’s a courtesy, not a luxury.”

Comments

See what people are discussing