The begging bowl mirror: Why India can’t afford to mock Pakistan

Is the Indian assertion that Pakistan is poor true? Let's take a look at the numbers

Asad Ejaz Butt

Guest Contributor

Asad Ejaz Butt is an economist based in Boston, US. He tweets @asadaijaz.

Pakistan does engage in a lot of external debt to remain afloat, but doesn’t India engage in debt, and perhaps, a lot of it?

Nukta Creative

As the dust settles on the Pahalgam story and war experts and defense analysts shift their focus to the Iran-Israel theater, it is perhaps a good time to evaluate, not the victory claims or losses borne by the two sides as popular media so engrossingly does, but an often overlooked aspect of such conflicts – something that I call a ‘narrative-crossfire’.

Speaking on the Piers Morgan show, Hina Rabbani Khar, Pakistan's former foreign minister, called India’s perspective on this war, and its view of neighboring Pakistan, the country’s narrative-framing, a term that has since caught up with Pakistani analysts.

Well, what is India’s narrative about Pakistan in the first place? Indians like to assert to the world that as India makes its economic ascent, its rival Pakistan drowns under the weight of the political economy of IMF programs and the vicious cycle of debt, which is what principally defines the opposing directions of the two South Asian countries.

I’m less interested in the politics that form the centerpiece of the Indian narrative and more in economics, which, as one could argue, should not have been the least discussed area of this conflict.

Indian journalists, diplomats, and government officials made headlines by collectively accusing Pakistan of hosting terrorist sanctuaries, training militants, and exporting terrorism, pointing to examples like Ajmal Kasab’s Pakistani origins and Osama bin Laden’s presence near a military facility in Abbottabad. They further claimed that Pakistan’s economy is in ruins and that it survives only by taking a begging bowl to the world, particularly from China and the IMF.

India’s economic stereotyping of Pakistan, and its implicit sense of entitlement, arrogance, and economic superiority, have powered its narrative of it being different from a ‘poor Pakistan’.

Numbers speak louder than words

However, the good thing about the discipline we are dealing with is that a dominant part of its theory ignores qualitative attributes like perceptions, feelings, and attitudes in favor of numbers and sheer numbers. And looking at numbers alone, it is hard to separate the economies of the two countries, other than size, which is also partly neutralized when one controls population.

It may also be difficult for economists to distinguish between India and Pakistan in terms of their tendencies to beg, which one may like to denote by the relative levels of public debt in the two economies.

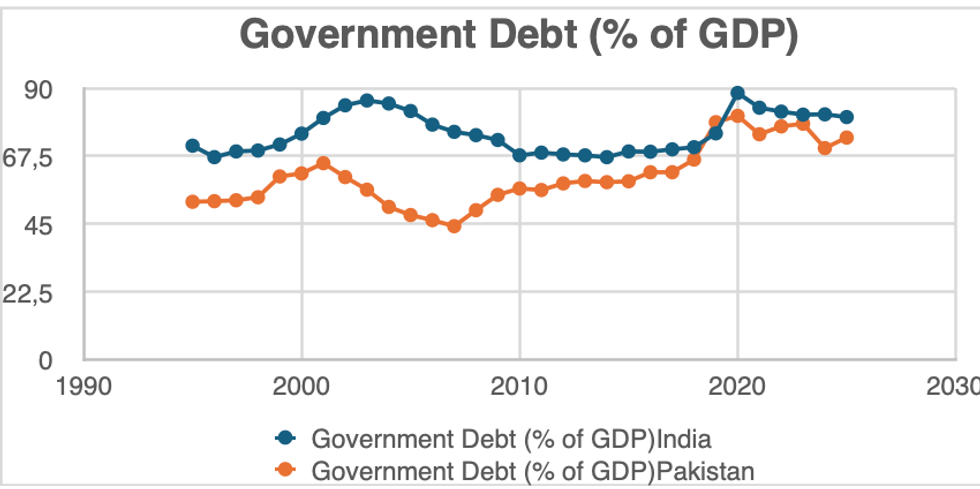

As can be seen in the chart below, government debt as a percent of GDP has historically remained higher in India than in Pakistan.

While the gap in the relative debt-to-GDP ratios has shrunk in recent years, closing up entirely in 2019, India's debt-to-GDP ratio today, at 80.4%, is considerably higher than Pakistan’s 73.6%. In India’s defense, a larger part of its debt composition is domestic debt, unlike Pakistan, as its recent budget also indicates that it relies more heavily on external sources like the IMF.

The domestic-debt heavy composition of overall government debt signifies at least one aspect of India’s debt policy, which is that it uses debt predominantly as an internal stabilizing instrument.

It may not require debt for balance of payments support, or to finance imports and build foreign exchange reserves, but to sustain fiscal operations, fund large-scale development programs, and manage budget deficits.

In FY 2024-25, the Indian central government had a fiscal deficit of 5.1% of GDP. While not too high, the persistence of deficits has led the central government to accumulate domestic debt. This situation is not very unlike some Indian states that are heavily indebted. Punjab, Bihar, and Kerala, to name a few, have been accumulating debt and adding stress to the Indian fiscal system.

While Pakistan’s external sector has remained vulnerable, pushing it to the brink of default in 2022, and into accepting stringent credit terms and belt-tightening reforms from the IMF, India’s external sector is not one without such vulnerabilities.

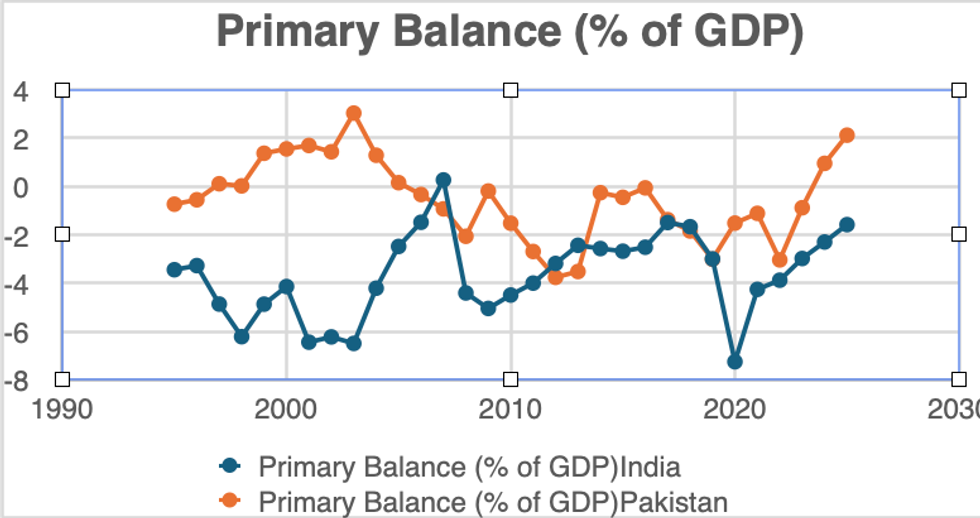

India’s primary balance, reflecting the difference between non-interest expenditures and revenues, is -1.58% of its GDP, while Pakistan, after experiencing a significant dip in its current account balance, has rebounded, thanks to a sharp rise in remittances, to a positive primary balance of 2.11% in FY 2024-25.

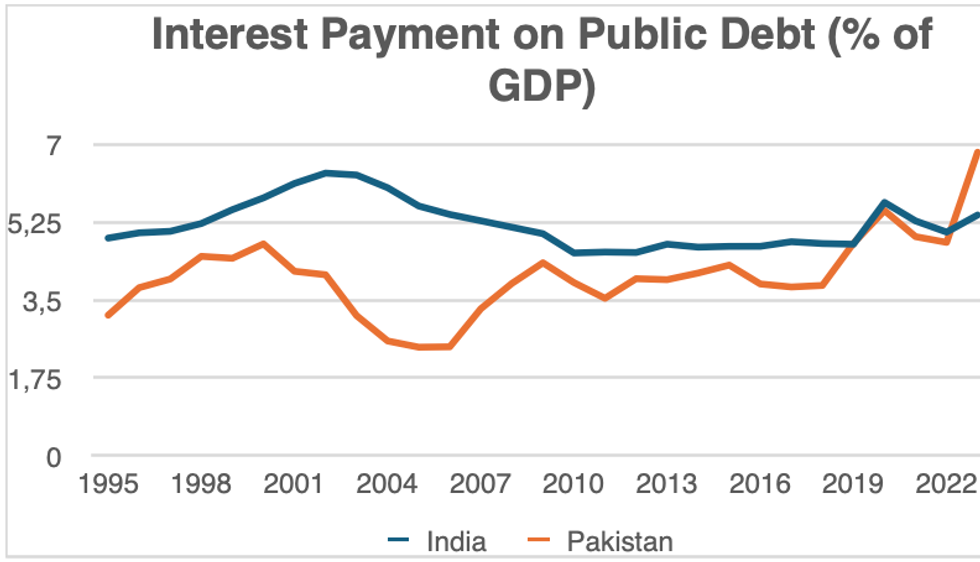

These dynamics are hardly disturbed even if one incorporates debt servicing and interest payments in the analysis. Interest payments, which have often been the subject of political wrangling in Pakistan, have only recently begun to outstrip the Indian interest payments.

Interest payments on public debt, historically higher in India, had stagnated in both countries during the decade or so before Covid-19.

They declined briefly after Covid-19 to rebound during the Russia-Ukraine war in FY 2022. This trend turned out to be much stronger in Pakistan’s case, which is now seeing almost half of its budget consumed by interest payments and debt servicing obligations.

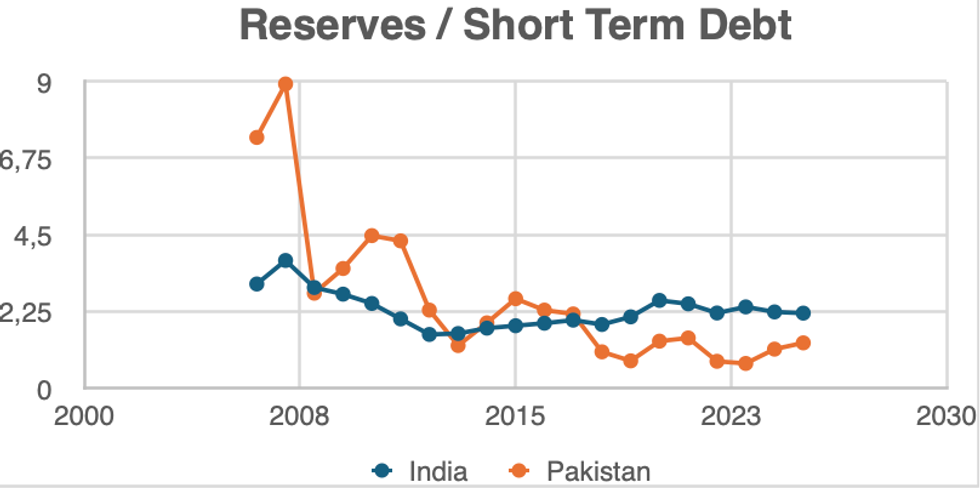

External sector vulnerabilities can also be looked at from the perspective of reserves and their relation to outstanding debt.

This indicates at least one important aspect of a developing nation’s economy, which is its ability to provide the foreign exchange cover for imports after servicing debt obligations, and more importantly, sustain international trade if debt isn’t available.

As one can see in the chart below, while India currently has higher reserves for each dollar of short-term debt, Pakistan has historically done better, only being surpassed by India in 2016-17.

India far from financial stability

But despite India’s recent advancements, it is far from achieving financial stability as its reserves have been experiencing a decline vis-à-vis short-term debt.

There isn’t really a very thick line that divides the relative abilities of the two economies to service debt and finance imports.

While India does better than Pakistan, only perhaps marginally so, on several social development (health, education) indicators, its magnificent growth masquerades a more sobering reality, which is manifested through many of its economy’s structural risks and bottlenecks.

The manufacturing sector, which is known to stimulate job creation and exports and function as a catalyst for economy-wide growth, is suffering from a capacity constraint that has grown over the years.

Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), which represents new investments in fixed assets like buildings, machinery, and infrastructure, has declined significantly over the years. It has dropped to 29.2% of the GDP in 2023-24 from its peak of 35.8% in 2007-08.

This is one of the main causes of stagnation in manufacturing growth, which only contributes 13.5% to India’s GDP and has remained nearly at that level in the last decade.

Corporate profits are available, but they aren’t widely distributed, concentrating in a few firms like Reliance and Adani that have gained monopoly status in their respective markets. This indicates weak implementation of competition rules, adoption of exploitative market practices, and constraints on resource mobilization and credit creation.

Similar structural constraints are plaguing other real productive sectors of the economy, for instance, agriculture, which is shaky in Pakistan too and suffers from similar productivity problems, contributes only 16.5% to India’s GDP while employing 42% of its population.

This reflects a profound problem of labor productivity that has persisted, and perhaps worsened. Policy uncertainty in the agriculture sector, like wheat and rice export bans in 2023, has led to a decline in agri exports, which may have further eroded capacity in this sector.

So who is poorer?

The Indian stereotyping of Pakistan as poor, however, is not entirely unfounded. Pakistan does engage in a lot of external debt to remain afloat, and therefore, one cannot blame the Indian intelligentsia for dubbing Pakistan’s external debt transactions as some kind of a begging bowl.

But doesn’t India engage in debt, and perhaps, a lot of it? External or domestic, while one may not want to equate the two, are only forms of debt after all, with their own peculiar ways of crippling economies.

Isn’t India poor? Well, it is. It has done exceptionally well to contain poverty in the last two decades or so, but as some Pakistani analysts contended during the peak of the Pahalgam conflict, India still hosts the largest number of poor people in the world and has the highest wealth inequality in Asia, with around the top 1% owning nearly 40% of its wealth. The same top 1% owns over 22% of the national income. Its GINI coefficient, which is a leading indicator of inequality in income or wealth distribution, has continued to rise in urban areas.

Economic growth has taken place in India, especially during the Modi years, but it hasn’t been inclusive; in fact, it won’t be unfair to say that some cohorts of the Indian society have grown at the expense of others, who have suffered.

Most GDP gains are cornered by the formal sector, while ironically, more than 90% of workers are still in the informal sector. India is a large economy and has improved on many counts, but claims like the one that Barkha Dutt, the Indian journalist, made on the same Piers Morgan’s show, that India is so economically successful today that if not for terrorism, it would like to ignore Pakistan, are both fallible and reflective of a deep sense of intellectual dishonesty.

*Asad Ejaz Butt is an economist based in Boston, US. He tweets @asadaijaz.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Nukta.

Comments

See what people are discussing