Pakistan’s madrassa registration debate: A clash of history, trust, and reform

Contentious madrassa reforms resurface in Pakistan, echoing deep-rooted mistrust and decades of historical resistance

Imran Kazmi

Senior Producer/Acting News Editor

Imran Kazmi is a seasoned digital journalist with nearly 15 years of experience in the media industry, including senior editorial roles at Pakistan’s leading news organisations.

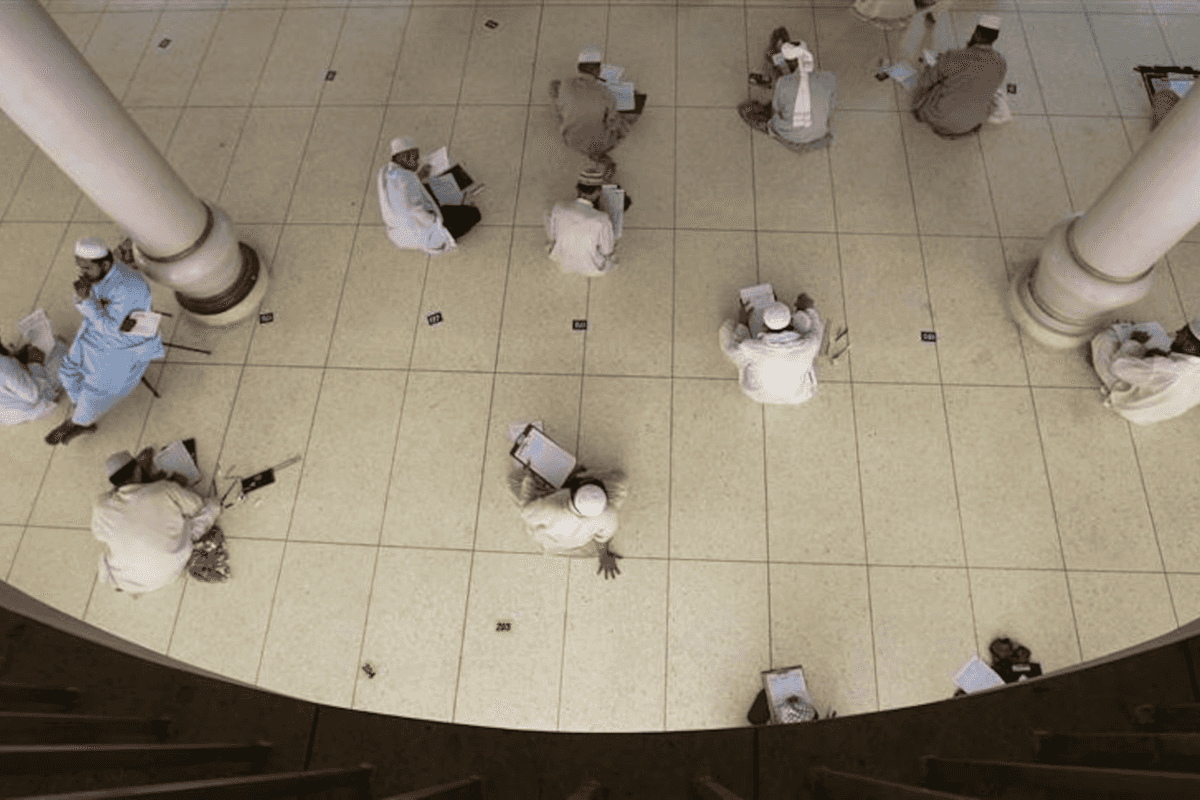

Students are seen taking mid-year exams at the Jamia Binoria Al-Alamia Seminary Islamic Study School in Karachi on April 29, 2009.

Reuters

Journalist specializing in madrassa education notes mistrust core issue, traces it back to 1857 War of Independence

Madrassa leadership fears losing their centuries-old role as guardians of religious traditions if autonomy is compromised

Religious scholar says no madrassa in Pakistan teaches a curriculum that encourages terrorism or provides terrorism for it

The debate over madrassa registration in Pakistan has reignited, laying bare decades of mistrust and historical complexities between religious institutions and successive governments.

The Societies Registration (Amendment) Bill, 2024, passed by parliament in October, proposes shifting madrassa registration from the Education Ministry to the Societies Registration Act of 1860. While the government calls it a procedural change, religious leaders and madrassa federations fear it undermines their autonomy and exposes them to international scrutiny.

“Trust has always been the core issue,” Sabookh Syed, a senior journalist with expertise in madrassa education, told Nukta. “This mistrust didn’t arise overnight. Its roots lie in the War of Independence in 1857.”

Historical roots of resistance

Following the 1857 rebellion, British colonial rule disrupted religious education systems, leading to the emergence of key movements: Darul Uloom Deoband, Aligarh, and Jamia Millia.

“Deoband declared opposition to the British, Aligarh tried to integrate with the colonial system, and Jamia Millia opted for moderation,” Syed explained. “That Deobandi stance of resistance against external influence persists to this day.”

After Pakistan’s independence in 1947, madrassas were treated as charitable entities under the Societies Registration Act of 1860. However, international dynamics, particularly after 9/11, shifted perceptions.

During the Afghan Jihad, both the United States and the establishment utilized madrassas. Later, they were also used for the Kashmir Jihad. But post-9/11, they became a target of international scrutiny. “The U.S. and its allies pressured Pakistan to regulate madrassas, linking them to extremism,” Syed said.

Reforms and resistance

The Musharraf government in the early 2000s attempted madrassa reform under the banner of “enlightened moderation”. A Madrassa Education Board was introduced, but religious leaders rejected it outright.

“Musharraf lacked legitimacy, and his reforms were seen as foreign-driven,” Syed noted. “The Lal Masjid operation, sectarian conflicts, and international pressure only deepened the divide.”

After the 2014 APS attack, madrassa reforms resurfaced under the National Action Plan. While some madrassas agreed to register under the Education Ministry in 2019, others clung to the Societies Act.

Syed explained why the resistance persists: “Madrassas fear losing their identity. They believe the government, under global pressure, may compromise their values and traditions.”

Current controversy

The new amendment bill attempts to reintroduce madrassa registration under the Societies Act, sparking renewed backlash. President Asif Ali Zardari withheld his signature, warning that bypassing existing laws could invite international scrutiny, including from FATF and GSP Plus monitors.

In his objections, Zardari cited “potential misuse of registration” and the risk of exacerbating sectarian divides. Religious leaders, particularly from Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F), dismissed his concerns as “baseless” and accused the government of “capitulating to international pressure”.

JUI-F chief Maulana Fazlur Rehman warned of protests if the bill proceeds without addressing religious leaders' concerns.

A trust deficit

For madrassas, the conflict isn’t just legal—it’s historical and cultural. Syed said this mistrust won’t vanish overnight.

“Governments fail to understand the madrassa mindset,” he noted. “Their resistance comes from years of viewing governments—first the British, then Pakistani regimes—as adversaries.”

He added, “The madrassa leadership feels that if their autonomy is compromised, they will lose their centuries-old role as guardians of religious traditions.”

Madrassas and terrorism

Addressing the perception linking madrassas to terrorism, Religious scholar Dr Amir Tuaseen said:

“I do not believe that any curriculum taught in madrassas fosters the concept of terrorism. However, internationally, madrassas have been accused of terrorism since 9/11. In the 1980s, during the Afghan war, many madrassa students participated in jihad based on their religious beliefs. But after 9/11, everything changed, and madrassas were unfairly linked to terrorism. This, in my view, is part of a propaganda campaign and a conspiracy to malign madrassas.”

He added, “I do not think any madrassa in Pakistan teaches such a curriculum or provides such training. That said, there have been isolated incidents, particularly in some madrassas in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab. However, accusing all 32,000 or 36,000 madrassas across Pakistan of such activities is grossly unjust.”

The path forward

Amid growing pressure, some madrassa leaders propose a middle ground. Mufti Abdul Rahim of Jamiatur Rasheed suggested allowing institutions to choose between registering under the Education Ministry or the Societies Act.

“This dual-track approach can ease tensions,” Syed said. “It’s pragmatic, but it requires trust-building, not coercion.”

Dr Tuaseen, speaking to Nukta, urged both opposing sides to set aside their “obstinacy and egos”. He suggested amending and improving the 2001 ordinance—under which madrassas are registered with the Ministry of Education— to make it acceptable to all stakeholders.

As the government navigates the fallout, the madrassa registration debate remains far more than a legislative issue. It’s a clash between historical resistance, international demands, and Pakistan’s evolving identity.

Comments

See what people are discussing