Why Saudi Arabia and UAE denying airspace won’t stop a US attack on Iran

From stealth bombers to submarines, the US can attack Iran even without relying on Gulf airbases

Zain Ul Abideen

Senior Producer

Zain Ul Abideen is an experienced digital journalist with over 12 years in the media industry, having held key editorial positions at top news organizations in Pakistan.

According to security analyst Syed Muhammad Ali, the American strike capability does not hinge on Arab airbases.

Shutterstock

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have publicly stated they will not allow the United States to use their airspace or bases in the event of an American attack on Iran. At first glance, that sounds like a major constraint on U.S. military planning.

In reality, it is not.

The statements come at a moment when the region is already on edge. Since the June 2025 U.S.-Israeli strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, tensions have steadily escalated, culminating in a major U.S. naval buildup near Oman and repeated warnings from President Donald Trump tied to Iran’s internal crackdown on protesters.

Against this backdrop, Gulf states appear less interested in shaping U.S. military decisions than in insulating themselves from the fallout of a conflict they neither control nor want to be dragged into.

US strike options without Gulf airspace

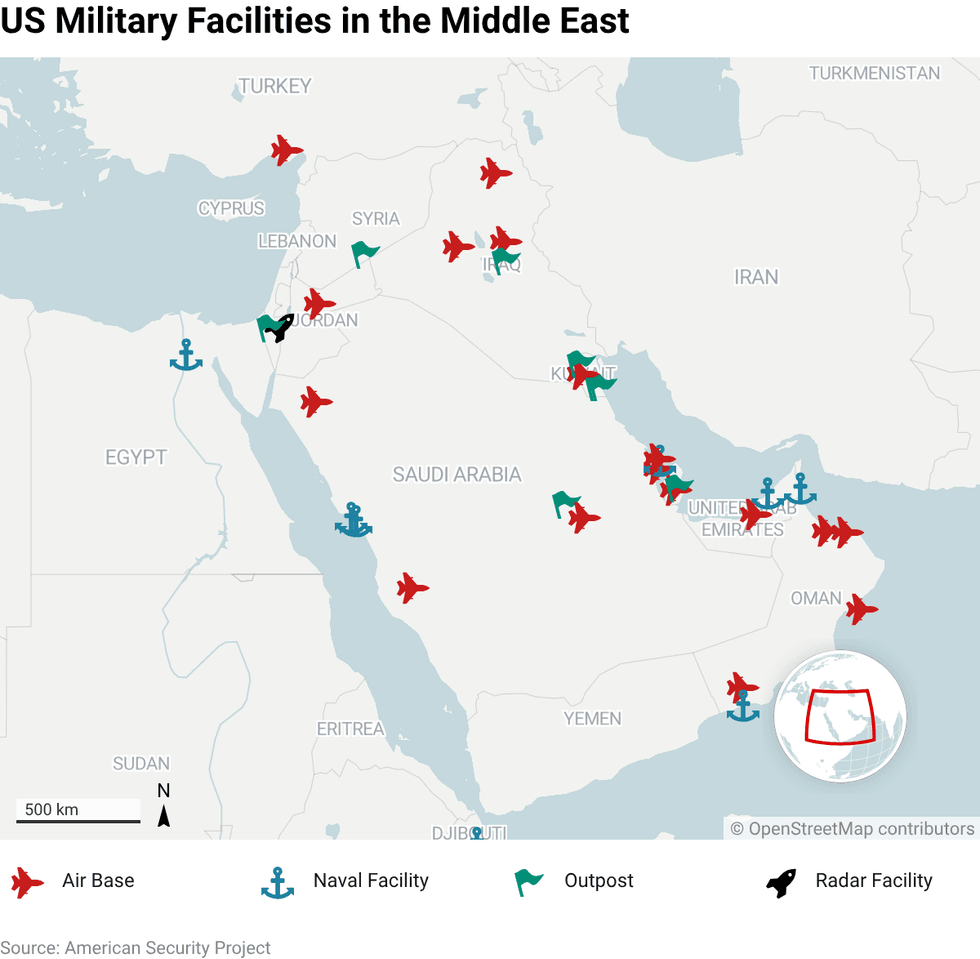

Speaking to Nukta, security analyst Syed Muhammad Ali said that denying access to Gulf airspace does little to diminish Washington’s ability to strike Iran if it has already decided to do so. The U.S., he argues, has deliberately structured its regional military posture to retain freedom of action — while simultaneously limiting Iran’s retaliation options.

The key point, Ali says, is that American strike capability does not hinge on Arab airbases.

“If the United States has decided to attack Iran, it does not require access to allied airbases or airspace,” he said. “It already has the capability to act independently.”

That capability rests on three pillars: long-range strategic bombers, naval power, and stealth technology.

The most significant asset is the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber. Deployed from Whiteman Air Force Base in the U.S. mainland or from Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, the B-2 can strike targets thousands of miles away without needing to land in the region. Mid-air refueling further extends its range, allowing direct missions into Iranian airspace and back.

Ali notes that the sensitivity of B-2 technology is such that Washington does not even deploy these aircraft on allied territory. Their use, therefore, bypasses political constraints imposed by regional partners.

Naval power provides the second layer. The USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group is currently positioned near Oman, with roughly 70 advanced combat aircraft onboard, including F-35 stealth fighters. Like the B-2, the F-35 is designed to evade radar, sharply reducing Iran’s ability to intercept incoming strikes.

The third pillar is the U.S. Navy’s missile capability. Several destroyers and at least two nuclear submarines in the region are estimated to carry between 1,000 and 1,200 Tomahawk cruise missiles. These can be launched within minutes against multiple targets inside Iran.

Taken together, Ali argues, these assets mean the United States can strike Iran without touching Gulf airspace or using Arab bases at all.

Why Gulf states are signaling restraint

So why, then, have Saudi Arabia and the UAE gone out of their way to publicly deny access?

Ali sees the statements less as pressure on Washington and more as strategic signaling to Tehran.

“These messages are aimed more at Iran than at the United States,” he said. “They are meant to tell Tehran that their territory is not being used against Iran — and therefore should not be targeted in retaliation.”

That distinction matters because Iran’s retaliation options are limited. Ali stresses that Tehran lacks the conventional military capacity to strike the U.S. homeland directly. Its air force, missile reach, and naval power are insufficient for that task.

Instead, Iran’s most realistic response to a U.S. attack would be targeting American bases, assets, and investments in the Middle East — particularly those located in Arab countries.

By declaring their airspace off-limits, Gulf states are attempting to remove the justification for Iranian retaliation on their soil. In effect, they are narrowing Iran’s target set.

This logic aligns with the broader U.S.-Israeli defensive strategy, Ali argues: degrade Iran’s ability to respond, not just its ability to strike.

Retaliation risks and limits of escalation

Recent history supports this assessment. During the June 2025 “12-Day War,” the United States intervened directly using B-2 bombers and submarine-launched missiles against Iran’s nuclear facilities at Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. Arab states were not directly involved, yet Iran still retaliated by striking the Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

That episode demonstrated both the reach of U.S. strike capabilities and the vulnerability of regional bases.

Today’s standoff is unfolding under even tenser conditions. Since January, Washington has reinforced its naval presence, while President Donald Trump has issued public warnings tied to Iran’s violent crackdown on protesters. Iran, for its part, has threatened “crushing blows” against U.S. bases if attacked.

What can China and Russia do?

Despite this rhetoric, Ali believes the risk of a full-scale state-to-state regional war remains limited.

“No country is realistically prepared to fight alongside Iran against the United States,” he said.

Russia and China may provide diplomatic backing and military equipment, but Ali dismisses the idea of direct military intervention as unrealistic. Regional states such as Pakistan and Gulf countries, he adds, are focused on de-escalation due to the severe economic and security fallout a wider war would bring.

The greater danger lies elsewhere.

Iran-backed armed groups — including Hezbollah, the Houthis, and militias in Iraq — retain the capacity to strike U.S. interests, companies, and installations across the region. Those attacks could significantly broaden the conflict without triggering formal state involvement.

That, Ali suggests, is precisely what Washington and Gulf capitals are trying to prevent.

By signaling non-involvement while the U.S. maintains overwhelming strike capability offshore and at long range, the message to Tehran is stark: retaliation will be costly, isolated, and difficult to justify.

Whether that deterrence holds is another matter. But one conclusion is already clear. Even if Gulf airspace remains closed, the United States retains multiple pathways to strike Iran — and has structured its military posture accordingly.

Comments

See what people are discussing