Why climate must stay out of the Pakistan-India crossfire

Ex-Indus commissioner warns that without cooperation, climate-driven floods will devastate both nations

Zain Ul Abideen

Senior Producer

Zain Ul Abideen is an experienced digital journalist with over 12 years in the media industry, having held key editorial positions at top news organizations in Pakistan.

Villagers wade through a flooded street following heavy rains at the Ehsan Pur village in Kot Addu district, Punjab province on August 21, 2025.

AFP

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed in 1960, has long been described as one of the most successful water-sharing agreements in the world. It has survived wars, standoffs, and decades of mistrust. But now, in the age of climate change, the treaty faces its sternest test: how Pakistan and India manage floods that are increasingly deadly, unpredictable, and politically charged.

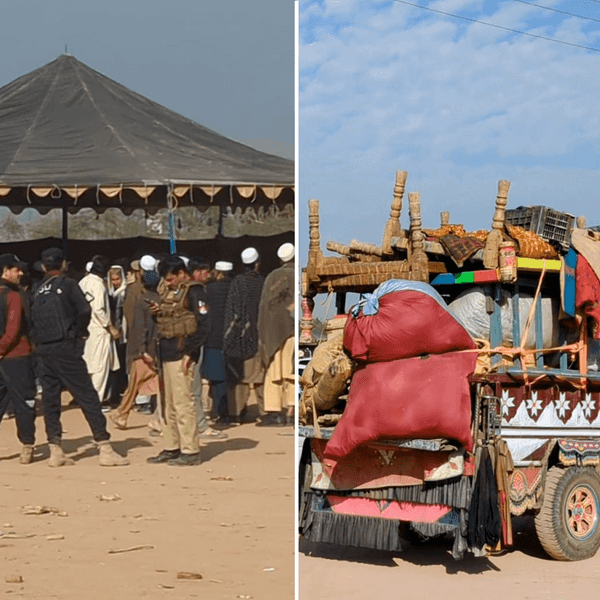

Pakistan recently evacuated at least 150,000 people from its breadbasket province of Punjab after India warned it would release excess water from a rapidly filling dam. The release, triggered by heavy rains in Indian Punjab and Indian-administered Kashmir, threatens to further inundate farmlands that sustain much of Pakistan’s food supply.

The alert came as both nations grapple with weeks of devastating floods. In Pakistan, nearly 800 people have died this monsoon season, half of them in the northwest province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Glacial melt has ravaged Gilgit-Baltistan, Karachi was partly submerged last week, and now Punjab faces the worst of the flood threat. India, too, has counted at least 60 deaths this month.

Against this backdrop, New Delhi’s decision to send a flood warning is striking—because just months ago, in May, it held in abeyance the Indus Waters Treaty after blaming Pakistan for a deadly attack in Indian-administered Kashmir. Islamabad denied involvement, but tensions escalated into the worst fighting in decades. By placing the treaty “in abeyance,” India cast doubt on the mechanisms that for decades ensured water cooperation even during conflict.

And yet, despite sidelining the treaty, India chose to alert Pakistan. An Indian official told Reuters the decision was made “on humanitarian grounds.” Islamabad acknowledged the warning but criticized that it came through diplomatic channels instead of the Indus Waters Commission, as the treaty requires.

Why flood warnings matter

For Pakistan, every hour of advance warning is crucial. Rivers like Chenab and Ravi can swell to dangerous levels within hours of dam releases in Indian Punjab. Without early alerts, Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and provincial authorities are left scrambling to move people from embankment villages into safety.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Syed Jamat Ali Shah, Pakistan’s former Indus Commissioner, told Nukta that historically, arrangements between the two countries allowed detailed, frequent updates throughout the monsoon season. “From July 1 to October 10, India would provide information even when water was low. As the flow increased, the frequency of information also increased,” Shah recalled.

This collaboration meant Pakistan could anticipate how floods would evolve. In 1989, the two countries agreed to telephone-based alerts, supplementing earlier telex messages and even paid radio broadcasts. Data on dams like Salal, Pong, and Bhakra was shared in real time.

But by 2013–2014, this system had collapsed. India argued Pakistan did not cooperate, and stopped providing additional data beyond treaty obligations. “That system was almost closed,” Shah said. Now, only the narrow requirement of Article 4, Paragraph 8 of the IWT remains: India must notify Pakistan of “extraordinary releases.”

This week’s alert, then, came under that limited scope. According to Shah, it lacked detail. “They only said there was a high flood in Tawi River, without specifying quantities,” he said. A “high flood” could mean three to four lakh cusecs of water—enough to put immense pressure on downstream structures like Marala Headworks near Sialkot.

Still, Shah welcomed the warning. “If we get early information, life and property can be saved. Pakistan should appreciate this step and move forward so that the IWT is fully restored,” he said.

Climate change is rewriting the rules

The urgency of flood cooperation is not academic. Climate change is intensifying South Asia’s water crises. Heavier monsoons, accelerated glacial melt, and sudden cloudbursts are increasing both floods and droughts. Pakistan’s vulnerability is acute: nearly half its population lives in Punjab province, where the Ravi, Sutlej, and Chenab converge after flowing from India. This is also the country’s agricultural heartland, producing staples like wheat, rice, and sugarcane.

This season’s evacuations highlight the stakes. Hundreds of villages have been cleared, crops are at risk, and any perception that India deliberately worsened flooding could inflame political tensions.

That is why humanitarian data sharing must be insulated from political disputes. Shah emphasized that flood alerts are not about national security but human security. “The data of floods is for the consumption of people. On humanitarian grounds, India had accepted this in the past,” he said.

Can Pakistan cope without India’s data?

Pakistan has improved its flood forecasting since the devastating floods of 1973 and 1988. Radars in Sialkot, Lahore, and Mangla allow the Pakistan Meteorological Department to estimate flows. But gaps remain. Sialkot’s radar, for example, cannot detect rainfall in Jammu, leaving blind spots for Chenab and Tawi flows.

“Our Met Department makes estimates, but without India’s quantitative data, our confidence level is lower,” Shah said. “When Indian data matched our assessments, our level of confidence increased.”

This dependency underscores the need for cooperative mechanisms. Other countries recognize this: China shares Brahmaputra River data with India during flood season. Why not Pakistan and India?

What should Pakistan do at home?

While advocating for regional cooperation, Shah urged Pakistan to strengthen domestic resilience. Settlements built illegally on floodplains and seasonal drains exacerbate damage during flash floods. “There should be legislation that there should not be any settlement in riverine areas,” he said.

He also called for investment in reservoirs to capture excess water, stronger civil defense forces under NDMA, and better early warning systems for cloudbursts and heavy rainfall. “Our mechanism for saving life and property is still weak. We rely too heavily on the army,” he warned.

The way forward

India’s decision to issue a flood warning—even if it is outside the treaty framework as claimed by India—should be seen as an opportunity to rebuild trust. For Islamabad, this means engaging New Delhi diplomatically, pressing for restoration of the Indus Waters Treaty in full, and encouraging data sharing not as a political concession but as a humanitarian obligation.

For India, it means recognizing that holding the treaty in abeyance does not diminish Pakistan’s dependence on upstream data. Climate disasters will not wait for political disputes to be settled.

“Water is going to Pakistan whether India likes it or not,” Shah observed. “If we treat it as a weapon, both nations will suffer. If we treat it as a shared lifeline, both can survive.”

The floods of 2022 displaced millions in Pakistan. This year, the monsoon has already killed nearly 800. If the two nuclear-armed rivals cannot cooperate to protect lives and crops from rising waters, then climate change—not war—may prove to be their most destructive enemy.

Comments

See what people are discussing